Traveling to Sullivan's

hile everyone on social media seemed to be making their first post-pandemic airline-ticket splurges on trips to Hawaii, in search of sun and sand, I headed in the opposite direction to warm up next to stacks of hi-fi equipment. I had heard rumors of an incredible (arguably incredibly over-the-top) system assembled by jazz fan Joe Sullivan in the Washington, DC, area -- a system curated and set up by Stirling Trayle of Audio Systems Optimized (ASO), a system that combined some of the finest components in the universe. So, naturally, I waited out the late summer, swampy, East Coast weather and booked a flight in October to visit our nation’s capital and gorge myself on great sound. I built a couple of extra days into my travel plans, mindful of the experience of journalist Ira Peck on his initial visit to the home of a young Thelonious Monk. Blue Note Records cofounder Alfred Lion’s wife Lorraine had suggested to Peck that she accompany him to make the introduction to Monk. Peck insisted on going it alone, and after ten minutes, he left the apartment, convinced that there was no story there, because Monk refused to talk to him. Peck’s editor sent him back, this time with Lorraine, and things went differently. With Lorraine’s help, Monk opened up like a flower, resulting in Peck penning a double-page spread that propelled Monk to an audience much wider than the small group of jazz insiders who frequented Harlem’s Minton's Playhouse, the jazz club where bebop was born. So instead of going it alone, I asked Stirling Trayle to make the introduction. While I didn’t anticipate any stalled conversations, Trayle's insights into the system, the setup and the whole process that produced it would be invaluable. Joe Sullivan, the owner of the system, is certainly more loquacious than Thelonious Monk, revealing an interesting and unusual path to audio nirvana. In addition to his day job as a Washington lawyer, Joe had maintained a side gig as a jazz guitarist. He befriended and took guitar lessons from well-known artists and regularly performed with groups around the Washington, DC, area for many years. A hand injury eventually impaired his abilities as a guitarist, so he settled on playing piano in the privacy of his home as his prime musical outlet, while at the same time he started taking an interest in developing a serious stereo system to help fill the void in his musical life. He had the space and resources to construct a dedicated listening room, so he hired the now-defunct Rives Audio to build one. He then started down the traditional path of building a system: visiting audio dealers to help him select equipment, filling the room with lots of treasure. Despite having sunk a small fortune into the effort, he was dissatisfied with the results but did not have the tools to identify the problem or figure out how to resolve it. He knew that he had spent a lot of money on a system that just did not deliver, and he also knew that continuing down the same rabbit hole was only going to lead to even greater disappointment.

That was when he read about Stirling Trayle, who had been getting a great deal of favorable press, here and in other publications, for his unique skills when it comes to setting up high-end systems. Based on the seldom-discussed fact that the vast majority of systems in the real world are underperforming, Trayle’s business model depends on his skill in taking those existing systems and adjusting them to release their full potential. His website advises that “buying new equipment is sometimes, but rarely, the answer.” Joe asked Stirling to figure out how the music could be freed from the shackles of his roomful of expensive audio equipment -- and equally expensive room. Spending time with Joe, Stirling set out to identify his goals for the system, during which period several things became apparent. Joe’s ears were attuned to real music, rather than hi-fi. He had played guitar and piano for many years and knew what live music sounded like -- from the inside. He was also exceptionally articulate, with a highly developed music vocabulary, particularly when it comes to jazz and its associated terminology. His experience with audio salesmen had made him “once bitten, twice shy.” He was also a good listener -- not just to music but to other peoples’ views and opinions. Finally -- and perhaps most crucially -- Joe was willing and able to spend whatever it took to build a music system, rather than assemble a mere collection of audiophile best-buys. As Stirling evaluated the equipment Joe had purchased from a series of different dealers, he could see that the main building blocks -- the speakers and amplification -- were irredeemably mismatched. He concluded that Joe’s system could never deliver what Joe was seeking and that nothing could be done to make it meet Joe’s needs. Stirling knew that he had to tell Joe that the only way to achieve his goal was to sell what he had and start from scratch. I can only imagine the lump in Stirling’s throat when he realized the unwelcome news he had to deliver. Instead of going into cardiac arrest at Stirling’s advice, or getting defensive and feeling invested in his mistakes, Joe was open to Stirling’s ideas. In Stirling, Joe found a bona fide advisor, somebody who was not simply trying to sell equipment. Stirling is neither a dealer nor an agent working on commission. He makes a living by charging for his time. Any recommendations he makes that involve purchasing equipment are based on what will sound good, not what will keep commissions/profits rolling in. The client actually buys the product from his dealer, with no kickback to Stirling. This puts him in a far better position to give an unbiased opinion -- and makes it far easier for a client to trust that advice -- advice that’s free of the influence of what’s on the floor, what offers the best commission or what needs to go if a dealer is going to meet his minimum sales with a given manufacturer. His knowledge base is not limited to the brands he represents for the simple reason that he does not represent any brands. It’s also incredibly broad, given the sheer range of different equipment and systems he works with.

And he knows how to extract the best sound from equipment. Based on Joe Sullivan’s room, goals, musical sophistication, willingness to spend what it took to achieve what he wanted and expectations when it comes to service, Stirling made recommendations and hooked Joe up with Ron Buffington of Liquid HiFi in South Carolina. Ron had already worked with Stirling on a few occasions and the two have formed a supportive and productive working relationship, one that leaves Stirling free to act as consultant and installer, while Liquid HiFi delivers additional input, onsite support and the traditional dealer capabilities that facilitate equipment assessment and service. Having established an outline brief for the system, Stirling and Ron worked with the manufacturers involved to establish a series of home auditions. Having validated the system proposal in terms of core equipment, they began the long journey to getting all the details just right. I spent two days observing and listening to Joe’s system. Notwithstanding, the fact that Stirling and Ron had made many trips to Joe’s room to set up the system, they were still in the fine-tuning stages. The first day of my visit was mostly devoted to watching Stirling crawl around on the floor adjusting things, like the various settings on the CH Precision equipment and precise speaker placement, going back and forth, comparing how the changes sounded. I used that time to take stock of the room and the inventory of equipment and accessories. Joe’s room is not one of those enormous, dedicated listening caverns you see pictured on speaker manufacturers’ websites (although it was considerably larger before the Rives room treatments were added). It is not small compared to what I or many of us audiophile use for a listening room, but it’s definitely compact in proportion to the money invested in equipment. At 14’ 2” wide and 21’ deep, the room is large enough for dedicated listening, but with Joe, his dog, Stirling, Ron and me in the room, it started to get crowded. The 8’ ceiling height is theoretically over 9’ high from an acoustic perspective, because of open venting in the ceiling construction, but it does limit the size of the speakers that can be used. The further Joe proceeded along the ASO path, the more he came to appreciate its rewards, ultimately leading to an entirely new suite of equipment. The room itself is the sole holdover from Joe’s earlier system. It is a fully enclosed, free-floating room with lots of wood and venting and curves to avoid resonances. Of course, I couldn't do a before-and-after comparison, but a couple of things were evident. The room was exceptionally quiet, and unlike in my California open-plan home, where air circulates freely, the room was dust-free. I began factoring in how many more hours I could listen to music if I didn’t waste time dusting components, shelves, CDs, and records.

The first things I took in when entering the room, once my eyes adjusted to all that wooden room treatment, were the substantial building blocks that comprise the system. Working backward (from an electrical standpoint) the system features Stenheim Alumine 5 SE speakers (with Nordost internal wiring, $72,400/pair). These are eye-catching for that most unexpected reason -- compared to the other components in the system, they are relatively modest in size and price. At about four feet tall and weighing in at 287 pounds per side, they pack a lot into a comparatively small package. As the photographs show, the front end of the room is dominated by electronics, leaving little space for larger speakers, and I imagine, no space for a subwoofer. Most audiophiles craving a dream system assume that it will include big, actually make that gigantic, speakers, but as I was soon to confirm, quality trumps size every time. Driving the speakers are a pair of CH Precision M10 amplifiers ($176,000 per pair), each a two-box affair. Each of the four boxes is seated on a custom HRS stand. The M10 amplifiers are arranged along the front of the listening space in between and slightly forward of the speakers, with a Computer Audio Design (CAD) GC-R grounding system ($24,500) in the middle.

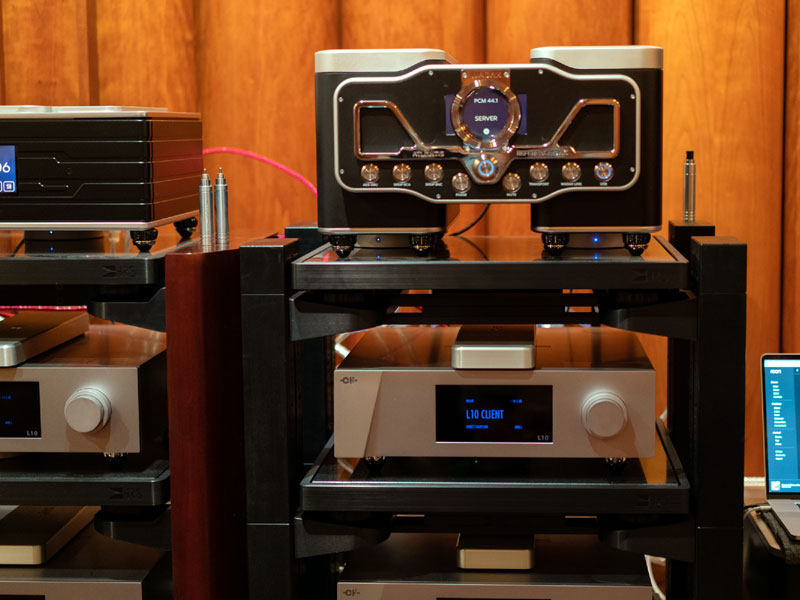

Switching sources and controlling level is a CH Precision L10 Dual Monaural Line Preamplifier ($126,000), also a four-box affair with separate left and right audio channels and power supplies. Completing the CH Precision lineup is a four-box phono stage, consisting of two P1 mono phono stages ($55,000 each) plus two X1 power supplies ($17,000 each). The front-end electronics are supported on two HRS VXR three-shelf, double-wide racks fitted out with M3x2 isolation bases ($100,560 total) and a three-shelf single-width rack ($33,520). From the left, the racks hold the two P1 phono units, with an X1 under each, then the four L10 units in a cube formation. Each of the eight CH Precision chassis is topped off with an HRX Damping Plate. Rather than using CH Precision’s built-in adjustable spikes, each of the eight boxes is supported by RevOPod Isolation Footers ($1295 for a set of four), as is everything else in the system, other than the amplifier and turntable. Hidden from sight beneath each front-end rack is a Nordost QB-8 QBase AC Distribution Unit ($2795 to $3650 each). Vinyl replay is handled by a Grand Prix Audio Monaco turntable ($37,950) with a Kuzma 4 Point tonearm ($11,500) bearing a Lyra Lambda Etna SL phono cartridge ($9995). Digital replay for Joe’s extensive CD collection is assigned to a Wadax Atlantis Reference DAC ($145,000) and Wadax Atlantis CD/SACD transport fitted with the special Reference AES/EBU + Ethernet digital interface ($59,800).

Hidden behind the racks is a second CAD GC-R grounding system as well as an extra GC-3 ($4500), each mounted on a custom HRS platform. Also, largely out of sight is the complete loom of Nordost Odin 2 interconnects, speaker cables, and power cords (the cost of which is in the “If you have to ask” category). What I soon came to realize, after briefly scanning the room, was that the plethora of little things adds up to so much. I noticed that two of the Damping Plates on the CH Precision Line stage were askew. I make liberal use of these at home and have discussed their placement with Stirling, who advised me to place them forward on CH Precision units, bridging the front panel. When I spotted the lack of symmetry in their placement (the two Plates on the lower L10 line stage boxes are placed further back than the other six Plates) I asked Stirling about the difference and learned that he had selected placement of them on each unit based on listening to various positions. Similarly, listening tests led Stirling to support the amplifiers on their own built-in spikes, while the other Ch Precision components (which have similar spikes) sounded better with RevoPods. The vast array of grounding devices took the same painstaking care and experimentation. None of the CADs or Nordost devices was included without carefully comparing how each unit sounded with and without the various devices attached. Joe’s listening habits are driven to a great extent by the music he spent so many years playing. Jazz recordings are heavily represented in his vast CD collection, with a much smaller selection of classical music. Of those jazz CDs, performances from the last quarter of the twentieth century up to the present dominate, and some of these (a fair few, in fact) feature artists he has played with or studied with. Throughout that first day of system adjustment, Joe would wander into the listening room on occasion. Stirling would run by him what he and Ron had adjusted, or what he proposed to change, playing segments of music to demonstrate the changes that he was making. Rather than simply nodding his head, Joe would actively comment and provide feedback on the changes he heard, underlining that this was a genuinely responsive and collaborative exercise. As Stirling frequently points out, he isn’t setting the system up for himself; he’s tuning the setup to match the owner’s tastes and preferences. With everything settled just so, I got to spend day two indulging my wildest listening fantasies. The bottom line is that this system sounded, in most ways, considerably better than any I have experienced. I recently spent time with CH Precision’s A1.5 amplifier, L1 line stage and P1 phono stage (the "entry-level separates") in my system, so in some respects I was not surprised by what the mother-ship system could do. Because of the relatively modest size of Joe’s room and the speakers, it does not reproduce the huge, walk-in soundstage that larger systems can present. But where it excelled over the competition was in realism. This is -- or perhaps should be -- the goal of every music-reproduction system, and it's a word we’ve all heard bandied about endlessly, but the effortless musical communication of this system placed it firmly in a league of its own. Sure, it did big music. The traditional test of a great system is symphonic music, and this system and listening room sounded remarkable with it. Records, CDs and SACDs -- many of the established reviewer and audiophile favorites, with a few of mine or Joe’s thrown in -- instantly unveiled an incredibly spacious musical experience, without flapping your trouser legs or rattling your ribcage, or transplanting the listener to the prairies or some vast cathedral. Instead it produced straightforward musical communication, just as live music does. But what I found shockingly engaging was small-scale jazz recorded in the early digital age -- in other words, CDs dating from the 1980s and 1990s. Granted, small-ensemble jazz recordings from the middle of the 20th century can sound good on most systems. Accepted wisdom in some circles is that they are therefore a poor test of a system’s ultimate abilities. It is also accepted wisdom that many (if not most) CDs from the first twenty or thirty years of the digital era are beyond any kind of musical or sonic redemption. Over the last decade, CD spinners have softened that blow, not so much making silk purses of sows’ ears but suggesting that those digital pits left much to be excavated -- something that’s rammed home in no uncertain terms by the Wadax units. I heard the Wadax DAC under show conditions, and Stirling and Roy Gregory had assured me of just how remarkable the current model is. But, as audiophiles know, hearing is believing, and now I’m a believer. Over and over, discs from this most dubious of recording periods defied their reputation and accepted wisdom to deliver some of the most intimate, engaging and sheer lifelike musical experiences I’ve ever had from an audio system -- bar none. Regardless of source or genre, this finely tuned system pretty much left the playback I’m used to in the dust. Joe Henderson’s The State of the Tenor, Volume 1, a fairly recent “Tone Poet” release on vinyl [Blue Note BT85123], is an extraordinarily fine live recording at the Village Vanguard from 1985. I have heard it in my system on tubes and solid state (including CH Precision’s A1.5 amplifier, L1 line stage and P1 phono stage) and it is of demonstration quality, no matter the system. But Joe’s system locked in the you-are-there quality like I had not experienced before without actually being "there," in a live setting. The opening minutes of Bruckner’s Symphony No.4 with Abbado conducting the Vienna Philharmonic [Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft 431 719-2] recently impressed me when listening at home on the “small” CH Precision system, but the size and detailed sonic picture on Joe’s system left little doubt that his money was wisely spent.

As with any visit -- and any experience this profound --

there always seems to be one moment or one disc that captures and encapsulates it. Given

the fact that the system was tuned to satisfy a jazz fan whose record collection is heavy

on music not available on vinyl, that moment happened with a jazz CD. That one CD that we

played over and again in the Sullivan listening room was Tony Williams Tough At Heart

[Columbia CK 69107], a 1996 recording made in Japan featuring Mulgrew Miller on piano. It

was Williams's last recording before his early death, with Miller in top form and Williams

playing a more subdued role than normal. The early-DSD recording sounded almost like

analog -- dare I say magical? -- on that system. Returning home I listened to the CD

again, and on an exceptionally good system, but it had lost its magic. Instead I found

myself pining for a ticket back to the East Coast. The cost of attaining the Indiana

Jones-like abilities of Joe's system to unearth musical treasure is daunting, but oh,

my God, have I found the system I want when I grow up. |