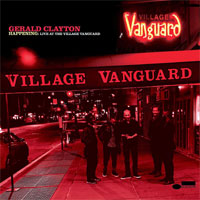

Gerald Clayton • Happening: Live at the Village Vanguard

The pianist gets two-handed and punchy, but isn’t a pounder; Clayton can lay back too, playing dappled lines in spritely rhythm. Swingy buoyancy is his birthright, as son of bass institution John Clayton. He always remembers to come up for air, and doesn’t let anything run too long; there are always other options. On “Celia,” one of bop piano patriarch Bud Powell’s “I Got Rhythm” variations, Clayton digs into the rolling intricacies of a written melody he obviously knows well; improvising, he leaves more open space, and varies texture and attack more than Bud would. (Of course Powell was purer: he was inventing a style.) Clayton can jab the low keys so you can practically see the hammers jump, or feather ghostly dyads behind a spun right-hand line. Alas, he may groan audibly in the pauses, sounding like he’s opening wide for a dentist. He’s hardly the only jazz musician to sing along with his own solos; he’s not even the only one in the band. Bassist Joe Sanders tracks his solos in loose oral unison, and per custom, that tic reinforces voice-like phrasing -- his improvisations are shapely, and he takes the breath pauses other string players forget -- but it also sounds a wee bit self-conscious. Four of the seven tunes are Clayton’s, and they present plenty of opportunities for give-and-tug interplay between Sanders and drummer Marcus Gilmore, who’s inherited grandpa Roy Haynes’s restlessly active textural variety and precision swing. It all comes together on ensemble tour de force “A Light,” twisty line with a Morse-code stutter in the rhythm that pervades the whole in various ways. Its key feature is a simple, effective ploy: Clayton replaces a customary string of long solos followed by 4-bar trades with a compromise: a round-robin of short-chorus solos (like, 17 seconds long) for piano and saxes, so they get to work off each other (as in conventional trades) and each gets enough space to develop a series of short solo statements. Smith sometimes jumps in on Richardson’s heels, so they squall together, but only momentarily. My friend Bill says that any band with two horns that don’t improvise together wastes an opportunity, and he’s not wrong. But that seems to be a free-jazz step too far. These guys are benders, not breakers. On live recordings, you can hear how the Village

Vanguard’s low ceiling soaks up applause. (It’s one way to identify recordings

made there.) And yet the music projects very nicely from the narrow end of that

wedge-shaped basement room -- there’s a reason a billion records get made there. (The

charging “Take the Coltrane” is a nod to that tradition -- never mind that Trane

recorded that one in the studio.) That low-ceilinged dryness works for the clear

uncluttered blended music, as recorded by Tyler McDiarmid and Geoff Countryman and mixed

by Jeremy Lucas with Sam Lararev. You could almost be sitting at a good-tipper’s

table -- without overhearing your neighbors’ drink orders. |

azz musicians now in

their mid-to-late 30s -- no longer new faces but not quite mid-career -- have had a

beneficial, broadening effect on the music’s big middle. It’s not just their

ease with hybrids between jazz and other genres. (Think Ambrose Akinmusire.) You also hear

that loosening up in tradition-minded sets like Gerald Clayton’s Happening: Live

at the Village Vanguard, recorded in April 2019, when the pianist was pushing 35. His

quintet/trio honor the tunes’ forms and the harmonies like certified jazzers, but

they don’t tear through them ferociously like 1980s Young Lions channeling ’60s

Miles Davis; Clayton’s approach is breezier, catches its breath a little more often.

He likes discursive solo intros that wander up to the tune, giving a written melody a

little advance buildup. When things are hot he might inject a calming interlude -- as when

setting up the drum solo in the middle of a searing version of Billy Strayhorn’s riff

blues with a hiccup “Take the Coltrane.” That one’s a romp for the twinned

saxophones who give this band much of its character: altoist Logan Richardson and tenor

ace and scholar Walter Smith III. Their blend can be plush or greasy or rough in good ways

-- they get guttural with little provocation. Smith is brusque and terse; Richardson can

spray squealing eels in the upper register, and sing with the melancholy sweetness of

Miguel Zenón. It’s a combustible mix.

azz musicians now in

their mid-to-late 30s -- no longer new faces but not quite mid-career -- have had a

beneficial, broadening effect on the music’s big middle. It’s not just their

ease with hybrids between jazz and other genres. (Think Ambrose Akinmusire.) You also hear

that loosening up in tradition-minded sets like Gerald Clayton’s Happening: Live

at the Village Vanguard, recorded in April 2019, when the pianist was pushing 35. His

quintet/trio honor the tunes’ forms and the harmonies like certified jazzers, but

they don’t tear through them ferociously like 1980s Young Lions channeling ’60s

Miles Davis; Clayton’s approach is breezier, catches its breath a little more often.

He likes discursive solo intros that wander up to the tune, giving a written melody a

little advance buildup. When things are hot he might inject a calming interlude -- as when

setting up the drum solo in the middle of a searing version of Billy Strayhorn’s riff

blues with a hiccup “Take the Coltrane.” That one’s a romp for the twinned

saxophones who give this band much of its character: altoist Logan Richardson and tenor

ace and scholar Walter Smith III. Their blend can be plush or greasy or rough in good ways

-- they get guttural with little provocation. Smith is brusque and terse; Richardson can

spray squealing eels in the upper register, and sing with the melancholy sweetness of

Miguel Zenón. It’s a combustible mix.