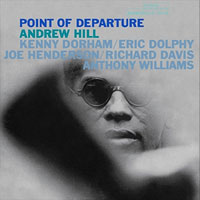

Andrew Hill • Point of Departure

Stanley Turrentine with The Three Sounds • Blue Hour

or seven years, the connoisseurs at Music Matters have reissued pairs of Blue Note LPs, each carefully chosen to be savored with the other, like wine with a main course. But a more dissimilar pair of albums than these two could not be imagined. Blue Hour, a smoldering set of blues ballads, stands at the opposite end of the musical spectrum from the adventurous jazz explored in the grooves of Point of Departure. On Blue Hour, Stanley Turrentine surrounds himself with one of the most popular jazz trios of the 1950s and 1960s, The Three Sounds, whose easygoing, fleet, blues-infused swinging endeared the group to many fans. Point of Departure, Andrew Hill’s third recording as a leader, is a jarring change of pace. Be prepared to be rudely awakened by the intense, fierce and unsettling but urgent music flying out of the grooves on this one. The mood of Blue Hour is, well, blue. The opener, "I Want a Little Girl," is sultry and slow, with Turrentine’s tenor miked so closely you can almost picture his vibrating Fred Hemke #3 1/2 reed. His dark, full-bodied sound is bathed in reverb, and for those into imaging, the sound you hear is a mirror image of the atmospheric cover photo. A smooth segue leads into the popular "Gee Baby, Ain’t I Good to You," which appears at first indistinguishable from the previous tune, so alike are the two in mood. But it is different, and all involved set the appropriate tone and pace. Drummer Bill Dowdy sounds as if he’s striking wafer-thin metal eggshells. This is the perfect song for that late-night glass of wine. The side ends with Gene Harris’s "Blue Riff," the only bona-fide twelve-bar blues on the album. Compared to the earlier cuts, its medium tempo is a gallop, but it fits perfectly with the overall character of the album. Side two brings us back to a slow drag on the lovely Budd Johnson ballad "Since I Fell for You." It’s turned into a quiet blues with great restraint shown on Turrentine’s part, as he caresses the theme with his robust, full-throated tone. There is nothing spectacular here, just solid performances by a group of veteran musicians familiar with tuneful playing. After a little over eight minutes of lovely sounds, including a brief fire lit under Turrentine toward the end, the song fades away. The album’s closer, "Willow Weep for Me," is taken uncharacteristically as a slow blues and moves like molasses. I have never heard the song played this way, but it works, and Turrentine displays some of his best and mellowest playing on the album. The rhythm section literally tiptoes through through the number. I enjoyed this record and found its atmosphere infectious. It would be the perfect music to play to welcome in the dawn after an especially reckless night of fun. My girlfriend also liked it, saying of Turrentine’s liquid tone, "Those notes fall easy on the ears." All of the tunes on Point of Departure are abstract and complex Hill originals, due perhaps to his years of study with classical composer Paul Hindemith. The ensemble players, major forces in modern jazz then or now, were chosen with their unique musical personalities in mind. After the opening bars of "Refuge," I was reminded of the line in the movie The Wizard of Oz: "Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore." Yes, indeed! The listener has left the mainstream far behind and is entering uncharted territory with but a sketch of a roadmap. The quirky, disjointed theme leads into an idiosyncratic solo by Hill peppered with angular rhythms and original harmonies. Eric Dolphy follows and contributes a scalding alto-sax solo seemingly materialized from another planet. Richard Davis sounds as if he’s trying to turn his bass into kindling during his amazing solo just before a return to the theme, after which tenor-sax man Joe Henderson introduces himself by squawking like a duck before settling into an invigorating solo. Amazing 19-year old drummer Tony Williams solos briefly and the tricky theme returns as the group brings the tune to a close. "New Monastery" is a jaunty, jerky tune with Monkish overtones. Unfortunately, trumpeter Kenny Dorham was not in particularly good form on this one, but Dolphy comes on like a hellhound on his short solo. Hill, as usual, gives a very personal solo. After a brief refrain, the tune ends abruptly. The exceptional quality of this recording draws the listener into the music by capturing many of the fine details of the performance: the differing resonances of the various drums, the metallic "thunk" and "plink" of hard wooden sticks on brass cymbals, the buzzing of acoustic bass strings against the ebony fingerboard, the decay of the piano’s notes as they escape the hammered strings. Side two opens with "Spectrum," a highly arrhythmic number with a theme buried in jumpy accents. Dolphy, in typical form (for him), almost shreds the bass clarinet in his solo. That he was able to tame such a hellish reed instrument is testimony to his patience and musicianship. A more refined Henderson follows on tenor sax, airing the closest thing to a traditional solo. Davis demonstrates that he was one of the most "in tune" bassists in the business on his solo, after which Dolphy takes an alto-sax solo dripping with deep emotion. After a short, bizarre ensemble passage, Dorham plays a muted trumpet solo followed by some extremely tentative, barely there drumming from Williams. The closest song to normalcy on the entire album is "Flight 19," a brisk jaunt of a tune featuring Hill's soloing, his fingers flying effortlessly across the keyboard. Young Tony Williams is fantastic on this cut. His subtle drumming perfectly complements the ensemble playing. The album’s closer, "Dedication," is a serene ode wrought with melancholy and strong (to me) Mingus overtones. Dolphy wails on his bass clarinet, providing a somber, reverential atmosphere to all that follows. It’s not surprising this tune was originally called "Cadaver." Hill’s sensitive, linear solo is supported by dreamlike horns providing the perfect platform for his cascading, deftly articulated piano. With all the fire and fury heard earlier, this song is the perfect elixir for restoring normalcy to derailed nerves. Music Matters has done it again with this pair of fine

reissues. The care lavished on them is evident from opening the gatefold cover and

admiring the exquisite Francis Wolff photographs, to removing the record from its

protective sleeve, putting it on the platter and, of course, playing it. Your ears will

perk up and your psyche will reboot. |