CH Precision • L1 Preamplifier, P1 Phono Stage and M1 Mono Amplifiers

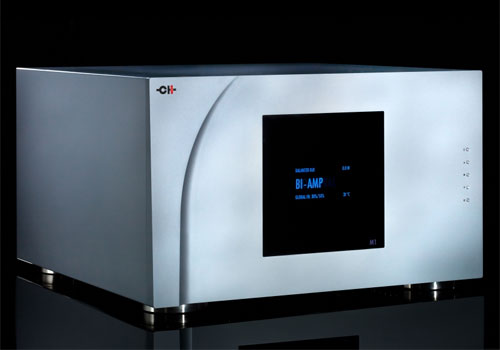

In my case, that experience started with the D1 player/transport and C1 digital control unit, delivered together with a pair of A1 amplifiers. It was a brave decision on the part of the company, as I’ve long expressed reservations about the whole concept of DACs driving power amps direct -- and the C1 didn’t do anything to change my view. The ergonomics were less than intuitive, and I could have lived without a lot of the cosmetic options. But what it did do, along with the D1, was demonstrate a performance level as a digital playback platform, especially with SACD, that was up there with the best I’d heard. The sensible array of practical options included in the power amps, facilities that allowed me to configure them for both the system topology and the character and nature of the load presented by the loudspeakers, had me wondering why more designers of solid-state equipment didn’t offer greater control over this critical interface. It was enough to tweak my interest and investigate further. A subsequent visit to the factory in Switzerland went a long way toward explaining both the company’s philosophy, the physical form of the products and many of the more unusual aspects of their operation. CH Precision is no ordinary company, and that’s reflected in the products they produce. Meanwhile, I’d had the chance to hear the rest of the product line, including one system containing the P1 phono stage, the L1 line stage and no fewer than four of the massive M1 amplifiers, deployed in mono mode (of which more later). Despite the price, despite the box count and despite the situation -- a cavernous room at the Lisbon show -- it was impossible to be anything other than seriously impressed. With the P1 being offered for review, the chance to include the L1 and M1 as well was just too good to miss, especially as the timing dovetailed perfectly with the arrival of the Stenheim Ultime Reference (CH Precision is responsible for the design and production of the Stenheim active crossover) and the Wilson Benesch Resolution loudspeakers (Wilson Benesch distributes CH Precision products in the UK and the products often share international dealers/distribution). If the D1/C1 combination risked setting off the Gregory alarm circuits, the P1, L1 and M1s sit much closer to my way of thinking. Even so, these are by their very nature, incredibly complex and configurable products, something made possible by their card-cage construction. It’s no accident or aesthetic conceit that so many of CH Precision’s products look all but identical. The casework is shared, a common chassis that can be configured to house the various motherboards necessary to construct each product. Then, on top of that, the number and type of inputs and outputs can also be user specified, be that the range and type of digital connections on the C1 or the number of inputs on the M1. Thus, each unit can be built to purpose, designed to suit an individual system and then reconfigured as that system changes. In a very real sense, you are buying the range of connectivity required -- and no more. Housed in CH Precision’s standard medium-height chassis, the P1 phono stage mimics the size and appearance of the A1 amplifier, with a large central display and five small buttons in a vertical row to the right. It’s a plain exterior that hides a highly adjustable and configurable unit, laden with options as standard. The P1 is equipped with three discrete phono inputs, each with balanced XLR and single-ended RCA connections. The single pair of outputs also offers balanced or single-ended connectors, as well as a pair of BNC sockets, an alternative analog connection option that is peculiarly Swiss, being found here and on the DarTZeel amplifiers, but nowhere else I’m aware of. Both the P1's MC1 and MC2 inputs operate in current mode, intended for use with low-output moving-coil cartridges. This unusual approach, which reads the current generated by the cartridge rather than the voltage, was highly favored by Dynavector, amongst others, which claimed a higher signal-to-noise ratio for the approach. It also renders impedance matching unnecessary, the gain of the transimpedance amplification stage being defined by the internal impedance of the cartridge: the lower the cartridge impedance, the higher the gain, an elegant, almost self-compensating system. The third input is a more conventional voltage-mode design, which can be used with low-output moving-coils but is also intended to allow use with moving-magnet cartridges or external step-up transformers. All three inputs offer gain adjustment, with the voltage input offering 35dB or 40dB for MM or transformer inputs, 55dB to 70dB (in 5dB steps) for MC. The sensitivity of the current-mode inputs can also be trimmed in 5dB steps, up to a maximum of 25dB, to further optimize noise performance, although the actual maximum gain will vary depending on the internal impedance of the cartridge. A 1-ohm internal impedance allows a maximum 80dB (+10dB) of gain, while with a 10-ohm internal impedance, that would drop to 75dB (+25dB). As well as variable gain, the voltage-mode input offers the next best thing to continuously variable loading, with a resistor ladder offering over 500 discrete values between 20 ohms and 100k ohms, covering pretty much any conceivable requirement, MC or MM. Along with the variable gain settings, that presents the listener with a mind-boggling range of options, but fear not -- help is at hand. The P1 Factory Settings menu includes a MM/MC Loading Wizard. Select the Wizard setting in the menu, set upper and lower loading values and then play the special 7" disc provided, a record that simply produces repeated frequency sweeps. The Loading Wizard will automatically select 20 different loading values, equally spaced between the upper and lower limits you’ve set, and store a frequency trace for each one. Once the process is complete you can scroll through the curves, selecting for flattest response -- while also playing your favorite test piece to see how each sounds. There’s no limit to the number of times you can repeat the process, setting progressively narrower upper and lower values as you zero in on your preferred setting. At the end of the day, you may or may not prefer the flattest and most technically accurate loading, but the graphic display is a really helpful aid in understanding both what is happening to the sound as you alter the loading and what sound you actually prefer. Side 2 of the test disc can be used with a similar Gain Wizard facility, also to be found in the Factory Settings menu, allowing the P1 to optimize each input’s gain for maximum signal-to-noise ratio and ideal output level. Finally, in the Audio Settings menu you’ll find a subsonic filter that can be individually selected for each input. That rounds out the range of standard settings available -- which is comprehensive to say the least. But it’s also far from the whole story. CH Precision also offers an optional internal card that allows users to select alternative replay curves beyond the RIAA and eRIAA equalizations provided as standard. Generic EMI, Columbia, Decca and Teldec curves can be selected via the front-panel buttons and menus, or more easily via the CH Control app, compatible with Android devices. Given the divisive nature of the whole record-replay EQ debate, this strikes me as the perfect solution, allowing those who want and value the facility to pay extra to get it, while not burdening those who can’t be bothered with or simply don’t want to know the cost of a facility they’ll never use. There’s also the option to run the P1 from the X1 external power supply. This shares the same casework as the P1 (save the five small push buttons) and can supply highly regulated DC for one or two CH components (P1, L1 or C1, the second output at an extra cost). The P1 can also be ordered as a mono device -- not so that you can play mono discs, but so that you can dedicate one P1 to each channel, the final step being the addition of another X1 to create a true-mono four-box phono stage. Outwardly, the L1 is the least configurable, least unusual unit in this lineup. Across all categories of amplification, from phono stage through monoblock amplifiers, the rarest beast by far is the world-class line stage. In fact, I can count the really great line stages I’ve heard on the fingers of one hand -- and one of those is the CH Precision L1. In some ways that seems slightly ironic, given that the company started out touting the virtues of the C1 digital control unit. But then, what better way to discover just how crucial the line stage is to system performance than to come up short trying to drive an amp from a DAC? The phrase "meat in the sandwich" describes the L1, and that’s about much more than L1's position in the system. Rather, it reflects the fact that so much of the meaty substance you get from these CH Precision electronics and so much of their musical authority emanates from the L1. Once again, we see irrefutable evidence that there’s no substitute for a great line stage. The same size, shape and format as the P1, the L1 shares the same large central display but substitutes a large, push-and-twist concentric control in place of the phono stage’s five tiny pushbuttons. It’s a less intuitive interface when it comes to setup, but then there are far fewer "in-play" options with the L1 once you’ve set the basic parameters, and volume controls really should be round. You get four balanced XLR inputs, two single-ended RCA inputs and two on BNCs. When it comes to outputs there are two balanced, one single-ended RCA and one BNC. You also get a USB port for software upgrades, an Ethernet connection for network control (via the Android app) and three earth posts that offer separate digital and analog grounds. The display color (on all CH units) can be selected from seven standard options or you can create your own custom RGB shade. The brightness is user adjustable and inputs can be individually named. A small handheld remote duplicates the five-button control layout of the P1, giving the owner access to volume, mute and input settings as well as a long-push phase invert -- pretty much everything you need. When it comes to electrical parameters, the L1 allows you to adjust individual input gain ±24dB in 0.5dB steps. You can also set individual input impedance (either 600 ohms balanced/300 ohms single-ended or a resistor-terminated high-impedance alternative) engage a DC blocking capacitor, select mono output, adjust balance by ±6dB. And establish switch-on volume and maximum level settings. Finally, you can also deploy the L1 in the same true-mono mode as the P1, to create a two-, three- or four-box line stage, with twice as many inputs and outputs. I ran both the L1 and the P1 from a single X1, in perhaps the most cost-effective of the various multi-box topologies. For most power amps, it’s unusual for the facilities to extend beyond a standby button, but the M1 is different. If, colored display aside, the configuration options available from the P1 and L1 have direct implications for system matching and performance, nothing displays the way in which CH Precision works to exploit technology to maximize performance better than their power amps. Built into a double-height chassis, with a double-height display, the M1 nevertheless shares the same styling, control logic and five pushbuttons as the P1. Inputs are the same balanced, single-ended RCA and BNC to match the other units in the range, while the Audio Settings menu offers no fewer than five operational modes plus a balanced daisy-chain option. Despite the positively misleading nomenclature, this is not a monoblock, merely a stereo amp that can be configured that way. The switchable modes allow the user to run the amplifier in stereo, mono or bridged configuration, passive biamp mode (one input fed to both outputs) or active biamp mode (where the channels can be individually configured). The percentage of local, as opposed to global, feedback can be adjusted in 10% steps from zero upwards, allowing users to adjust damping factor, while the amplifier gain can be adjusted by ±12dB in 0.5dB steps to match speaker sensitivity. Given the ruinous price of M1 ownership, giving customers the idea that it’s necessary to own two of the amps just to get started could be considered detrimental to sales. In fact, running a single M1 is a very real (and seriously impressive) option, allowing later upgrades to additional units if or when funds allow. In stereo mode, the M1 is rated at an extremely healthy 200Wpc. Mono is even healthier, delivering the same rated power but drawing on the entire power supply, while in bridged mode the amp can deliver 700 watts of (less load tolerant) power. Like the other CH Precision components, the M1 is equipped with USB and network connections to allow updates and remote operation, something that is extremely useful given the range of system configurations there are on offer. The ability to adjust feedback (damping factor) remotely was especially welcome. The input boards are modular, meaning that those going straight to a mono or passive biamp setup can dispense with the unnecessary connections. The ability to daisy-chain both inputs and amplifiers as a whole suggests a predilection for multi-box systems and offers the ability to simplify their wiring. Squat and visually imposing (although not unattractive) at 75 kilos, the M1 is just about single-man movable. In keeping with their building-block philosophy, CH delivered two of the beasts, allowing me to try them in all the various modes, but specifically the active biamp topology necessary for the Stenheim Ultime Reference loudspeakers. With all those electronic gymnastics on display, it’s perhaps inevitable that somewhere along the line the designer or software engineer is going to over-egg the pudding. Under the circumstances, the "light show" color options on the CH Precision displays are forgivable -- to be filed under "a bit of fun and no damage done." However, unlike some design teams that suffer from technological tunnel vision, CH Precision has made a genuine effort to leave absolutely no stone unturned in their pursuit of performance -- and that includes the mechanical aspects of the products. From mechanically floated transformers to massive, precision-machined chassis parts, they’ve definitely gone the extra mile.

On paper, that all looks good; in practice, it fails to deliver and it’s not hard to understand why. Harsh? Let me make the case. First, nobody spending this sort of money on amplification should be neglecting proper investment in supports (at least not if they want to actually realize the performance they’ve just paid for), and even if the notion of a furniture-free stack might seem appealing, no manufacturer should be encouraging it. But more important, not only do the spiked posts fail in their primary role, even with the units stood on individual shelves or platforms, they are actually detrimental to performance. Heavy and magnetic, they don’t lock, allowing them to rattle; they have considerable unsupported length, which encourages them to resonate and being steel; they interfere with the delicate circuitry and the signals its carrying. Why go to all the trouble of machining casework out of aluminum if you are going to build a steel "fence" inside it? The saving grace in all this is that it’s easy to demonstrate both the spike's malign influence and to eliminate it. Simply listen to the units deployed as recommended and then bypass their spikes with alternative supports (I used HRS Nimbus footers). The benefits in terms of noise floor, rhythmic articulation, focus and transparency are hard to discredit. As usual, experiment with the placing of the footers and you can gain further benefits. All of which suggests that while the corner posts pay lip service to the concept of mechanical grounding, they are neither ideally positioned nor actually effective -- just the existence and effect of those polymer discs should set the alarm bells ringing. The coup de grace comes when you remove the posts altogether; just listen to the soundstage expand while tonal colors and harmonics bloom. The conclusion is simple -- the grounding posts are best left in the boxes in which they arrive. It’s not often that a design weakness in any product is as easily rectified.

he versatility of both ends of this electronic chain (not to mention the sheer stability of its central anchor) made for an unusually wide and successful range of partnering systems. I was able to run the P1 with cartridges as varied as the Lyra Etna (0.56mV output, 4.2-ohm internal impedance), Fuuga (0.35mV, 2.5-ohm internal impedance), Ortofon MC 7500 (0.13mV, 6-ohm internal impedance) and the Cartridgeman Musicmaker Classic (a 4.0mV output-variable design based on a Grado generator and intended to see a 47k-ohm load) -- which is quite a range. At the other end of the chain I got to use the Stenheim Ultime Reference in both passive and active modes, the Wilson Audio Alexx and the Wilson Benesch Resolution, with and without the Torus subwoofer. Although the speakers might look superficially similar -- all tall, multi-way, multi-driver boxes -- their technologies and electrical characteristics are really quite different, with the Alexx offering higher efficiency but a far more demanding load while the Wilson Benesch offers a virtual first-order, two-way configuration but far lower sensitivity. Meanwhile, the Stenheim is really two speakers in one, the passive version showing the M1s’ ability to grip a full range load while the active option (complete with CH-built crossover) demonstrates both its versatility and absolute quality. The first thing to say is that, despite the range of cartridge output levels and the 6dB variation in speaker sensitivity, I never had any trouble with overall system gain. Second, the range of adjustment available meant that I could always optimize gain for musical performance, aiming to run it around the 0dB setting on the L1. Changing cartridges was most easily achieved at the line stage input: changing speakers, I altered the power-amp gain instead, making sure that the volume levels for both the record player and Neodio CD player stayed equivalent. Talking of changing speakers, the adjustable feedback ratio really came in handy. Both the Alexx and the Resolutions worked best with the amps set at 10%, as did the Stenheims in passive mode, but switching to active, reducing the feedback ratio on the midrange and treble to 0% showed a serious musical benefit. So far, using both the A1 and the M1, I don’t think I’ve ever set the ratio higher than 10%, which leaves me wondering whether CH Precision might improve things still further by offering 2% steps between 0 and 20, rather than 10% steps between 0 and 100. That could get seriously interesting, especially with the sort of full-range speakers that are likely to be used with these amps. The P1’s Loading Wizard was certainly an interesting option, although, as suggested, it really only gives you a starting point, there being more to cartridge/system matching than a flat frequency response. Its real value lay in the establishment of a series of closely grouped, graphically illustrated options that you can switch between, making the final choice easier and considerably less hit-and-miss. For many users, I suspect that the Gain Wizard might actually have greater long-term value, given the propensity for audiophiles to reach out for as much phono gain as they can get. However, what was never in doubt was the musical and sonic superiority of the current-mode inputs. The MM/MC input came into its own with the Musicmaker -- and turned in an impressive performance full of the presence, energy and musical enthusiasm that characterize this cartridge -- but with the moving-coils, the current-mode inputs offered greater body, flow, musical articulation, grace and color, making the MC/MM input sound thin, grainy and mechanical in comparison. I should also applaud the provision of multiple, independent grounding points (on all CH components) along with 4mm posts with butterfly nuts on the end to ensure a really good contact. It’s another really useful tool in terms of optimizing the system noise floor, understanding that each unit is but a part of the greater whole, yet it’s overlooked by the vast majority of designers/manufacturers. Sonically, the P1 sits firmly in the high-resolution, ultra-transparency school of solid-state phono-stage design. It’s quick, clean and incredibly lucid at the note-to-note level, clearly defining the attack, weight and sustain of each note, the space between it and the next note in line and the space around the instrument. If the P1 has a natural peer, then it’s the Tom Evans Master Groove, sharing that unit’s ability to place instruments in space and relative to each other, as well as placing them in the same space as you. There’s a stark immediacy to the P1’s presentation that is both dramatic and impressive in the way it brings instruments to life, especially when fed by the Fuuga. Piano is properly percussive, yet at the same time the poise and magisterial grace of a player like Michelangelo Benedetti emerges to make the melodies dance and the contrasts hit home. Compare that to Barenboim playing the Mozart Piano Concertos (with the ECO [EMI 1C 197-52 249 60]), all characteristically quicksilver fluidity and pace, the notes tumbling forth yet somehow keeping their feet in a display of virtuoso speed and balance -- yet one that ultimately lacks substance. Now switch to Beethoven (the Emperor Concerto with Klemperer conducting the New Philharmonia [EMI ASD 2500]). The orchestral playing is typically measured, almost ponderous in its weight and towering dramatic purpose, but against its backdrop, Barenboim’s playing is one-dimensional and mechanical, lacking expressive emphasis or dynamic punctuation. It’s a comparison of two players and three performances that underlines just how clear an insight the P1 provides when it comes to technique and performance. If you want to know how something is being played -- and how well -- then the CH Precision P1 will never leave you in doubt. Another piece of Mozart is a perfect case in point. Eine Kleine Nachtmusik is so hackneyed, so overplayed and so often dumbed down that it’s far from the first piece you’d reach for when investigating a system’s expressive and musical capabilities. Yet Decca captured a sensational performance by Munchinger and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra [Decca SXL 2270], full of dramatic contrast, musical brilliance and with a real sense of purpose in the playing. The sure-footed agility and attack of the strings are scintillating, the mathematical perfection of the interlocking phrases and clarity of the counterpoint too. But what lifts this performance another notch when you play it through the P1 is the absolute clarity, precision and power of the double basses. Timbre and texture are spot on, as is the sense of attack or restraint that pushes the music forward or holds it perfectly in place. It’s a masterclass in controlling weight and energy at points across the entire frequency range, an ability that revels in the vivacious quality and infectious drive of this remarkable performance. Just as the P1 separates the relative performance of different players, so it differentiates between different cartridges. Use the Fuuga and you’ll marvel at its effortless sense of substance and musical power. Switch to the Etna and suddenly the system is all about balance and the inner relationships between players, instrumental identity and musical contrast, the P1 allowing, even encouraging, each cartridge to give of its best. The depth of its resolution might make you favor the richer run of cartridges, from Lyra onwards, rather than the current Ortofons, for example, but whether it’s a Clearaudio or a Koetsu, the P1 will offer a constant reminder of what made you choose that cartridge in the first place. Although, having said that, it’s ironic that I’ve actually probably had the best results ever out of the Ortofon MC 7500 playing it through the P1. Okay, so it’s a long way from current -- and it’s probably the last Ortofon that I really, really liked -- but the P1 underlined in no uncertain terms just what a great cartridge the '7500 was. Despite the cartridge's highish internal impedance, the P1 still had enough quiet gain via its current-mode inputs to handle the cripplingly low output, delivering the presence, dimensionality, natural perspective and subtle tonal palette that are its hallmarks. That’s an impressive result and casts the P1 in an important light, given the recent move amongst cartridges like the Fuuga, Lyra Etna and Lyra Atlas SL versions, back toward fewer coil windings and lower outputs. Throughout the listening the ability to toggle back and forth between the appropriate replay curves was a musical godsend. As usual, the impact on performance and performances was much more than simply tonal, and those who dismiss replay EQ as nothing more than a tone control really are missing the point. If we take the legendary Menuhin/Philharmonia recording of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto [EMI ASD 334] as an example, engaging the EMI curve brought more than a tonal correction. It brought spatial and temporal coherence to the soundstage, added bite, brilliance and attack to the playing, and life and presence to the performance of both soloist and orchestra. This was always a good recording, but having the correct replay EQ lifted it considerably, elevating Menuhin’s playing to the truly great, his beautiful control of the bow, fast or slow, perfectly balanced by the poise and tempo of the orchestra. This is the difference between a decent record and a captivating experience -- exactly the sort of difference that equipment at this price level should make! As a predominantly classical listener, whether playing records from Decca, EMI or DGG, I found the ability to switch EQ was invaluable in revealing the performances captured in the recordings. Just look at the artist rosters on those labels and it’s pretty apparent that there are great performances. Of course, the need to switch EQ will depend on the nature of your record collection, but anybody who values early pressings, classical, jazz and, to a lesser extent, pop, should investigate the option seriously. For me it is indispensable and CH has got both the execution and the accessibility spot on. At the other end of the electronic chain, the M1 does a mighty job with the minimum of fuss or intrusion. Even a single M1 is a stellar performer, offering good dynamic range, superb focus and transparency, and brilliant bass definition, all with the minimum of audible effort. Indeed, driving the Wilson Alexxes, a single M1 was more than adequate to meet their demanding load. Yes, a second unit running in mono increased dynamic range, bottom-end transparency and sheer grunt, but nowhere near to the extent that justified the cost. It’s a result that, faced with the Wilson’s awkward load (and liking for power) underlines just how capable the M1 is. As the Stenheim experience demonstrated, the option to run a pair of stereos is much more musically rewarding, the active option with the Ultime Reference proving spectacularly successful. Likewise, with the Wilson Benesch Resolutions, the stereo pair again outperformed the monoblock setup, this time without the benefit of an active crossover, but mirroring previous results achieved in the A1/Endeavour setup. It’s a compelling argument in favor of biamping and makes the M1’s stereo mode all the more important. In many ways, the M1 is a classic high-powered solid-state design, with all the attributes you’d associate with the breed: It’s evenly balanced, transparent, focussed and stable. But even by the standards established by the best of the competition, the M1 is both remarkably imperturbable and incredibly deft. Despite the power available, you simply don’t hear this amp working, and it exhibits none of the hesitation, lack of fluidity or stilted dynamics that so often signal the presence of oodles of solid-state power. Of course, 200 watts isn’t exactly mega power, but it’s what stands behind them that counts, and the M1 is definitely all there. You’ll hear its power delivery in the crescendos, but where you really hear this amp’s quality is in the slow movements, those subtly evolving soundscapes that depend so completely on the mastery of level and tempo -- and which so cruelly expose most solid-state pretenders. Run a slow movement into a burgeoning crescendo and you have a perfect storm/ On which subject, what better example than the opening prelude to RVW’s Sinfonia Antarctica (Boult, LPO and LPC [EMI ASD 2631])? This is music that swells from the ground up, bold, dramatic and imposing -- yet slow, stately and powerful too, as dependent on quivering delicacy as it is on sweeping gestures. Any hesitation in the dynamic response, any tonal thinness robbing the sound of presence and body and the piece lacks power and the ability to fix the listener. With the M1s doing the driving, the opening had exactly the right mix of towering majesty and brooding threat, the building crescendo rising to a properly shattering conclusion. There‘s no escaping the beauty and danger of this soundscape. Whether it’s the rest of the Sinfonia Antarctica or Shostakovich’s 5th Symphony (Berglund and the Bournemouth S.O. [EMI SLS 5044]), the M1s' ability to conjure the stark cold of desolation or the white heat and rich passions of explosive emotions is equally effortless. At no time does the soundstage tumble forward, and there’s no tendency for instruments to climb with pitch or level. The amps’ stability is total and totally independent of demand, and I never managed to provoke musical or sonic collapse, no matter how hard I tried (and believe me, with this much power and speakers like these on tap, you can’t resist trying). But there’s more to great music than the loud bits, and the M1s do delicate just as well. In fact, their ability to preserve the intimate, to project and discriminate energy levels, large or small, across the entire bandwidth, even in the face of huge conflicting forces is an object lesson in just what a great solid-state design should offer. There are those who -- perhaps unkindly -- point to Herbert Von Karajan’s limited number of concerto recordings and suggest it has more than a little to do with his unwillingness to share the spotlight or relinquish control. His opera recordings suggest that isn’t so, but then maybe opera singers are larger than life in every sense and he can stand the comparison. But amongst instrumentalists, successful partnerships have been few and far between and maybe it takes a performer with the stature of a Rostropovich to command HVK’s respect. Certainly, the pairing’s Dvorak Cello Concerto [Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft SLPM 139044], recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic, is the exception to the rule. Of course, selecting the appropriate EQ on the P1 is essential, but with that done, HVK’s control over level and tempo is faultless and what seems like a slightly slow pace to start merely adds to the drama and impact of the opening tuttis. But the revelation is the entrance of the solo instrument. Overvoiced in the recording style of the day (helping it to balance the powerful orchestral playing), Rostropovich’s cello is bold and present, yet full of expressive range and subtlety. There’s a sinuous structure to his playing, taut and precise, ripped and rippling in its muscular tension, and the M1s revel in and reveal both his supreme technique and its contrast with the richer, lusher, more romantic readings of Starker and Piatigorsky on Mercury and RCA respectively. Much of this has to do with the amplifiers’ ability to track tiny shifts in the level and intensity of the playing, but it also shows, if not a weakness, then a characteristic of their reproduction. Much of the delicacy and intimacy in the playing are revealed by the amps’ emphasis on the strings, as opposed to the body of the instrument, the structure of the note rather than its core. The result is a sound that leans toward focus and separation, air and stability, rather than the solid presence, full-throated body and power of an amp like the VTL Siegfried IIs. Don’t go getting the idea that the M1 sounds wimpy (nothing could be further from the truth), but what I’m suggesting here is a leaning or tendency -- one that’s not out of step with the technology on which it’s based. What is really remarkable is that it’s only a tendency -- that the solid-state nature of the M1s isn’t more apparent, its musical impact more obvious. Instead the amps make the most of their strengths while mitigating their weaknesses to such an extent that their nature is almost if not invisible, then irrelevant. Talking of invisible, perhaps it's time to touch on the sound of the L1, or maybe not. In as much as any product I’ve tested could be said to be devoid of a sound, the L1 is it. It allows you to select a source, match its level and set the volume. The rest of the time is spent simply getting out of the way. If you should only notice a subwoofer when you switch it off, you should only notice a line stage when it isn’t there, and on that basis the L1 is that rarest of beasts: a line stage that really does pass unnoticed -- right up to the point when you remove it from or replace it in the system. But before we get into what the L1 does and doesn’t do, it’s time to mention the X1 external power supply. It's a fit-and-forget option, and once you’ve decided whether you want your X1 to supply one or two audio units, simply connect the umbilicals to the sockets provided on the L1 and P1 (or C1, if you have one) and switch the power supply and both audio boxes on. The P1 and L1 auto-sense the presence of the power supply and react accordingly. You do, however, still need to connect their AC cords, as these power the control functions. Adding the X1 is, quite frankly, a no-brainer. Given the price of a P1 or L1 and the difference wrought to their performance by the X1, at its relatively -- at least in the world of CH Precision-- modest cost, it should be an automatic add-on or urgent upgrade. The drop in the noise floor that results from its use has profound musical implications, both in dynamic and expressive terms. Performers have greater presence, their playing greater agility. The soundstage expands and snaps into focus and the instruments in the orchestra, or voices singing, are better separated, both spatially and tonally, the latter a function of a wider and better-differentiated tonal palette. Your correspondent forced himself to undergo the necessary listening to confirm these results across different recordings and genres, but, frankly, it was a relief to return to the system fully X1-ed. Except that I guess it wasn’t "fully X1-ed," in the sense that I could have added another one if it was available. I’ll leave that thought for another day, but it’s an avenue that I can’t imagine any CH Precision owner, having heard what a single X1 can do, will leave uninvestigated for long. In the meantime, you can assume that the performance described here, for all the units under review, is what they delivered with the X1 in the system. The reason I mention the contribution of the X1 at this point is because, more than any other musical factor, its impact on the L1’s dynamic response and headroom is key to the line stage’s ability to pass unnoticed -- to pass a signal, free of compression or gating. It makes the CH Precision electronics extremely impressive when things get loud and dynamic jumps can be as sudden and shocking as required. But the same quality that works so well when the music is loud and proud is, if anything, even more crucial when things get low and slow. Having commended the M1 for its ability to move through slower-paced passages with grace and without dragging its feet, it’s also necessary to acknowledge the crucial part the L1 plays in that performance. The amplifier can track and preserve those subtle shifts in tempo or lifts in level, but they must be preserved and passed by the line stage before they even get to the amplifier, and it’s in this role that the L1 excels. With its dynamic fluidity and ultra-low noise-floor, it provides the temporal and dynamic reference plane for the whole system, the bedrock on which the musical performance rests. The solidity of that reference is what gives the system its stability, and from that stability everything else grows, whether it’s the rhythmic security that allows expressive range, or the stable reference that allows us to appreciate tiny shifts in level and attack. As I’ve already stated, you hear it in the system’s ability to musically grow or accelerate, to jump or turn on a dime -- but you really hear it in the fragile beauty of a decaying melodic line, the downbeat close of an aria, a player’s slowing before launching into a new phrase. The result is a sense of unquestioned and absolute musical authority, the confidence that musicians have the time, space and skill to perform, that no musical nuance will pass unnoticed, that no demand will prove too great. In reality, that level of performance simply isn’t possible, but with the L1 in control, the CH electronics manage to kid you that it is (and probably themselves too). To appreciate just why the L1 is such an impressively stable and commanding presence, you need to look at the care that’s gone into its creation, from the digitally controlled volume ladder that eliminates DC from the switching process to the steps taken to eliminate DC from the source components. Realizing that small DC offsets are a regular byproduct of even the best relays, CH Precision has equipped the L1 with circuitry that constantly monitors the presence of DC, not just in the volume control ladder itself but throughout the circuit, allowing CH to eliminate it with small inverse voltages applied at the output. As well as dealing with self-generated DC, this also eliminates DC entering the signal path from external sources and source components. For those sources that generate more DC than the compensation circuitry can deal with, each input is also equipped with the option to switch in a blocking capacitor. These exhaustive steps, along with the extensive regulation built into the fully balanced design and backed up by the X1, indicates the lengths that CH Precision is prepared to go to in order to create this oasis of sonic calm, not a murmur or a ripple disturbing the environment in which the signal will arrive and through which it will pass. A line stage may only be a source switch and a volume control, but not all switches and definitely not all volume controls are created equal. Throughout the period I’ve had the CH Precision electronics in-house, I’ve been constantly aware of two things that set them apart. On the one hand, they truly represent a system approach to electronic design, the different elements and their attributes combining to create a remarkably engaging and immersive musical experience. As sonically correct and operationally faultless as they are, there’s nothing sterile or unfeeling in their performance -- or if there is, it’s because they haven’t been fully optimized. In one sense, that’s their burden: They’re effortless in revealing musical workings, but equally effortless in revealing any shortcomings in their own setup. Play with the feedback percentage on the power amp and you’ll see what I mean. It’s very easy to kill the sound of this system, to overdamp and crush the life out of it. But when it sings, it sings with a beautiful and powerful voice that’s unmistakable. It’s not as simple as the whole being greater than the sum of the parts, because individually the parts remain remarkably capable and impressive. It’s more that they bring the best out of each other, both through shared attributes and consistency. Indeed, consistency is one of their great virtues and one that it’s easy to overlook. Once set up and sorted, this system sounds the same, day in, day out. That might seem like an unusual commendation, but believe me, one of the major frustrations with many really expensive components is their variability -- brilliant one day, oddly off-key the next. Not the CH Precision pieces, which have been utterly stable, fuss-free and musically consistent throughout. You simply leave them on and let them do their thing. And do it they do. Which brings me to my second observation: normally when looking at sets of electronics like this, there’s one piece that stands out, one that stands above the others. With the CH components, that doesn’t happen. It’s not that they are all equal, or equally good; rather, as your attention shifts from one element to another, as you set up the phono stage for a new cartridge or dial in the amps with a new set of speakers, so you find yourself thinking, Yes, this is the one -- this is the best thing that CH builds. Yet, as soon as you move your focus, so that impression shifts with it. It’s not something I’ve ever noticed before, and it suggests to me that not only are these great products to work with, both in terms of what they offer operationally and how they respond to input, but that the quiet star in this constellation is the L1 line stage, whose simple excellence elevates all of the products around it. There has been another contributing factor to the performance I’ve enjoyed from the CH Precision electronics. I’ve already mentioned the variety and quality of the speakers on hand, stellar performers all. What I haven’t talked about is source components. I got to run the P1 with both the Kuzma Stabi M and the Grand Prix Audio Monaco v2.0, both models of analog excellence and sonic rectitude, record players that add little of themselves and excel in allowing the cartridge to do its job. But the absence of additive elements combined with the absolute timing precision of the Monaco 2.0 proved a particularly potent match with the CH Precision pieces, mirroring and heightening their own attributes perfectly. If the CH electronics excel in preserving the signal they’re fed, then the Monaco 2.0 gives them exactly the sort of signal they like. But I also used the set up with CD replay from the Neodio Origine S2 and again, the L1/M1 combination fastened on the sense of musical flow and expressive intimacy that make this player so special. Both serve as a timely reminder not just that the CH electronics are only as good as the source you feed them, but that they’ll also give you every last ounce of what that source has to give.

For dedicated analog users who demand more than one cartridge and more than one replay EQ, the P1 sets a new standard of both performance and versatility. The M1 power amp is simply the most musically accomplished, high-powered solid-state piece it has been my pleasure to use. I love its configurable nature and I love the idea of adding additional amps along the way, even if the cost of just one of these is beyond my means. One M1 or two A1s? Definitely the M1. It has a confidence and stability, a freedom from constraint at either end of the musical range that is rare indeed. Which leaves us with the L1, the least outwardly special but, quietly, the most impressive and fundamentally musical product here. Used individually, any of these units

will, by turns, astonish, beguile, impress and entertain. Used together, I have no doubt

that this is one of the finest and most musically complete electronic chains currently

available. It is also by its nature, one of the most musically consistent. The cost of

ownership is horribly and unattainably high and, given the ability to seemingly expand

each and every component ever further, almost without limit, but for those who can afford

it, the performance will -- and will always -- justify the price.

|

|||||||||||||