Vinyl's Home Office

arrived in Salina, Kansas, on a blisteringly hot day -- 103 in the shade and the air heavy with humidity. Chad Kassem invited me to tour his newly minted record-pressing plant, but I ended up seeing every corner of his growing business and in the process spent one of the most memorable days of my time in the audio press. The tour of Acoustic Sounds, Quality Record Pressings and Blue Heaven Studios, which comprise Chad's analog empire, was a reminder of the power of music and the uncompromising standards that drive high-end audio. The lead-in groove

bout every third audiophile you mention Chad Kassem's name to has a story that begins "I've been buying records from him since. . . ." In the early 1980s, after discovering how good carefully mastered and pressed LPs could sound, Kassem began selling B-stock and remaindered Mobile Fidelity LPs via the mail. These were the early days of the CD, when vinyl's demise seemed all but assured. "The business began in my apartment," he reminisced, "moved to my house, then to small offices, then to a bigger building, and then to an even bigger building." Over the course of the past seven months, Acoustic Sounds has more than doubled its space. Last December, the company moved from a 18,000-square-foot facility that comprised offices and warehouse space to two separate buildings down the street from each other. The office building is now 21,000 square feet, while the warehouse is 28,000 square feet -- big enough to be traversed by golf cart.

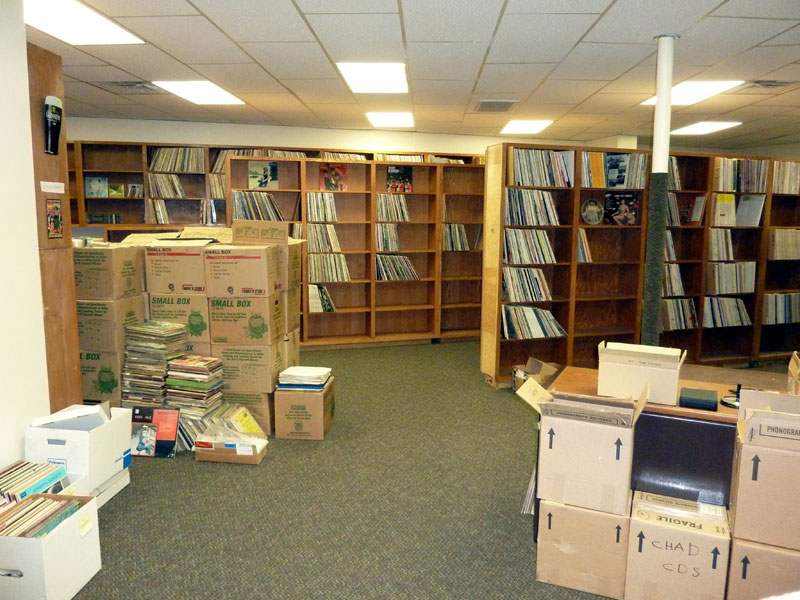

Some of the 46,000-record purchase and a few shelves of the Acoustic Sounds Vinyl Vault. Records are everywhere at Acoustic Sounds -- on desktops in offices and on countertops in the break room. There are piles of boxes stuffed with them, and row upon row of shelves filled with them. They even hang from the walls as decoration. During my visit, I kept seeing parts of a 46,000-classical-record collection that Chad purchased strewn about the building. One of the Acoustic Sounds staff was holed up in a corner inspecting these records, scanning their covers and adding them to the company's website -- one record at a time. Nearby, Paul Chester (shown below), whose name you may recognize from the Acoustic Sounds catalogs, listened to test pressings. "I make money selling records, and I spend money making records," Chad quipped, and Paul is an important part of this effort. He pulled a test pressing of an upcoming release from its plain white sleeve, started it spinning on a Technics SP-10 Mk II turntable -- chosen not for its audiophile pedigree but because of its quick stop-start abilities -- and sat down to listen, not to the music but rather to what was happening beneath it. He makes extensive notes, recording the point on each track where a tick, pop or other anomaly exists. And get this -- he listens to at least four test pressings of each title, cross-referencing what he hears on one with what he noted on the others.

The point of such attentiveness is making better records. Immediately before my visit, Chad had decided to redo an upcoming release because of one faint tick that was on the lacquer and transferred to the stamper. "People don't know about this stuff," he told me, referring to the thousands of dollars Acoustic Sounds will spend to remove that single bit of noise. Chad's office is a miasma of projects-in-progress and music, always music. He has a serious audio system here: Spendor S100 speakers, a pair of VTL mono amps, a Sutherland preamp and a Kenwood K-07D turntable that I immediately coveted because of its two tonearms.

When Acoustic Sounds announces the release of a series of Verve or Impulse! titles, Kassem hand-picks them. He had boxes of Verve and Columbia records in his office -- all from his personal collection -- and was sifting through them, deciding which titles to release. The criteria is simple: if he likes a record, he puts it on the list. In terms of jazz, Chad admits to preferring "straight-ahead" titles -- ones whose merits are immediately and easily understood. He eschews experimental and avant-garde titles because he simply doesn't like that music as much. As he flipped through the boxes, he told me which titles he had decided upon, and why, remarking, "I'm glad when other companies release records that I like. I can't do them all, and at least I'll be able to get a good copy." Half of his record collection is housed in a concrete bunker adjacent to his office. There have to be 7000 records here, with another 7000 at his house.

We should all be so lucky as to have a Kenwood L-07D with two tonearms in our office system. The Acoustic Sounds warehouse is immense but orderly, and it's wirelessly networked to the offices, where the orders originate. As we rode on a golf cart from one end to the other, Chad stopped to point out particularly interesting stock, like the 30,000 sealed records he purchased a number of years ago. These included 200+ original Verve titles, which have long been sold. Interesting titles remain, including obscure records from jazz greats and a large number of movie soundtracks, some of which have been long forgotten.

The records on other rows of shelves are easily recognizable by the identifying marks of their spines: black and orange stripes for Impulse!, all white with black lettering for Blue Note. We drive by and the patterns repeat with perfect regularity, like rows of corn in the summer. Digital has its own area, as do the various audio products Acoustic Sounds sells -- amps, turntables and record-cleaning accessories. In the middle and to one side is the packing area, large rolls of bubblewrap and piles of cartons decorating the ceiling and walls. Four people pick and pack up to 300 orders a day. The records of record

ext door to the warehouse is the newest addition and the main reason for my visit. Quality Record Pressings (QRP) completes the music-production circle that begins with recording the artists (more on that in a bit) and ends with the sale of their records. It is in many ways the most precarious part of the process. Designing and constructing any kind of manufacturing facility is a laborious undertaking, and the obstacles multiply when the facility you're building will press records. It's not as though you can buy the hardware out of a catalog. Record presses and plating equipment haven't been made for decades, and what's available needs repair and repainting at the very least and may require top-to-bottom restoration. Added to this is the ambition that Kassem and his staff have. "Put a million dollars in this hand," Chad said, holding out his right hand. "Put the ability to press the best records in the world in this hand," he said, motioning with his left hand. He reached out his left hand and said, "I'll take what's here." Where does that "million dollars" figure come from? That's all he would reveal about his financial commitment to Quality Record Pressings -- so far. Even a quick glance around the 21,000-square-foot plant reveals where that money has gone. The building began life as a colossal refrigerator for the storage of food. Before any equipment, fixtures, plumbing or electrical could be installed, entire rooms had to be stripped of foot-thick insulation and then repainted. When you walk into the large pressing area, you notice air filters affixed to the doors. It's a clean room with constant airflow to remove airborne particles. This makes sense, given that dust is an enemy of analog playback. What also makes sense is a modification made to the presses. The chassis of each is cut in order to isolate the motors and hydraulics -- which are sources of vibration -- from the press itself. This rests on industrial-grade absorbers. There are currently six operating presses, two each from Toolex Alpha, SMT and Finebilt. Each is at least 30 years old. The Toolex Alpha and SMT presses are automated, the workhorses of the plant (as well as the Pallas and RTI plants, respectively). The Finebilt presses are manual and feature a couple of important add-ons. Temperature probes in the dies along with programmable logic controllers monitor the pressing process, allowing for greater control over the minute conditions required to make records, especially thicker ones. And that's what the Finebilt presses will be used for -- the modern equivalent of JVC's renowned flat-profile UHQR pressings, each of which the operator will edge-trim and inspect immediately after it comes out of the press. Pressing records in this way is as much art as science, and it requires people with a deep understanding of the entire process. With this in mind, Chad hired Gary Salstrom and Mark Huggett, who worked at the Wakefield pressing plant in Phoenix, Arizona, until it closed in 1989. Salstrom went on to work at RTI in California, where Chad recruited him for QRP, while Huggett was coaxed out of retirement. Salstrom, who is plant manager, has the reputation of being one of the finest plating technicians in the world, and Huggett, who's an audiophile, "just knows more than anyone," according to Salstrom, about pressing records. Other modifications done to the presses are aimed at smoothing out inconsistencies in the heating/cooling cycle and the contact of the vinyl with the stampers, which Quality Record Pressings also creates, normally the same day the lacquers are received. The plant is already doing plating and pressing for labels other than Analogue Productions and APO Records, Acoustic Sounds' house labels. Still, the bulk of the plant's output at this point is over twenty Analogue Productions titles, including many double-LP 45rpm sets from the Verve catalog. Pews & blues

fter the pressing plant, Chad took me to Blue Heaven Studios. I suppose this austere red-brick building is technically a converted church, but at this point, more than a decade after it was purchased, it still looks as much like a place of worship as a recording studio. Its abundant well-wrought woodwork is matched by its expansive acoustics, which you notice as your voice carries through the immensity of the main floor. Kassem claims that even seats in the last row of the balcony -- when it was built, this was the equivalent of today's megachurches, though smaller and imbued with far greater character -- are still in the sweet spot.

Blue Heaven is quiet for much of the year, coming to life for direct-to-disk recording sessions and the yearly Blues Masters at the Crossroads festival, which transforms it into a commotion of music and food à la the festivals in Chad Kassem's native Louisiana. The festival features as many blues notables as can be accommodated over a weekend, and its past roster is a who's-who of modern blues players, many of whom have passed away since the festival launched fourteen years ago. The walls are decked with their pictures, underscoring the preservation of their music that is an important part of the studio's mission.

The view from the balcony of Blue Heaven Studios. As Chad walked around his studio and relayed all that happens during Blues Masters, it was easy to sense that this festival held each October is one of the proudest and most joyous moments of his year. Hearing and believing

ollowing a whirlwind day that covered everything from retail sales to record pressing, Chad took me first to Acoustic Sounds' previous home, where the company's reference system resides while listening rooms are constructed in the new building. There were actually a pair of adjacent listening rooms in the old building, both of them measuring 18' wide by 33' long. The front room was nearly empty, while in the back room a pair of Avalon Sentinel speakers draws immediate attention. I had never heard these speakers, which include their own bass amps, but they retained Avalon's stock portrayal of extreme spaciousness, driven by a Pass Labs stereo amp. The music Chad played -- a few of his direct-to-disk LPs -- was astonishingly detailed and dynamic. It was delicate at one moment, knock-you-over powerful the next.

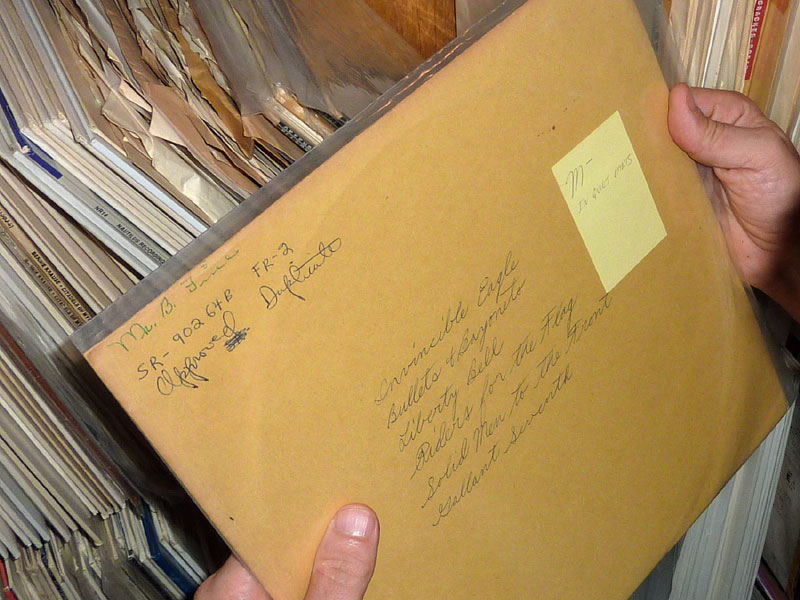

Kassem also uses Avalon speakers in his home system. He drives Eidolons with Sutherland mono amps, a Sutherland preamp and phono stage in front of these, and a Basis turntable with Graham tonearm and Shelter cartridge as the source. This occupies the front two-thirds of the room. In the back are the rest of his LPs -- easily the finest collection I've ever seen. This is understandable, I suppose, as Kassem has been an inveterate LP collector for his entire adult life. He has most well-pressed audiophile LPs ever made, including dozens of Mobile Fidelity test pressings and some titles MoFi never released. Even rarer were test pressings of Mercury Living Presence releases once owned by recording engineer Robert Fine.

Sound treatment between the speakers courtesy of Chad Kassem's four-year-old daughter. Chad is not shy when it comes to playing any of these, but we listened to test pressings of Analogue Productions and APO Records releases instead. He played DJ, choosing a truly eclectic mix of music. Highlights included Nancy Bryan's sophisticated singer-songwriter folk-pop and Dan Dyer's blues-gospel-chamber rock -- amazing stuff in both musical and sonic terms. Like the Sentinels, the Eidolons were expert at melting away the walls of the room and replacing them with an absolutely cavernous and supremely detailed soundscape.

"Mr. B. Fine" is Robert Fine, renowned recording engineer for Mercury Records. We listened past midnight, the vibe reminding me of when

I was much younger, getting together with friends and playing the latest records we had

bought. This is uniquely an analog thing, the drop of the stylus signaling that something

special is about to happen so pay attention. It's easy to think the same thing

about Quality Record Pressings as its LPs make their way beyond Salina, Kansas, and out to

the rest of the world. |