Linn

at Home

Today the company is run by Gilad Tiefenbrun (above), son of Ivor, who started the company 40 years ago last February near Linn Park in Glasgow. The current factory is outside that city and surrounded by green fields with cows grazing in them, a picturesque locale for a high-tech engineering company.

The first bit of the building you get to see as a visiting journalist is the Linn Home, a very plush, open-plan area that's divided into living, eating, sleeping and studying areas. This effect is achieved largely with furniture alone, and each area has its own networked music system, so the bulk of the current Linn product line is present. There's a Klimax DS and Klimax 350 active, or "Aktiv," speaker system in the lounge and a Kiko system in the study. There's even a Sekrit system in the en-suite and kitchen areas. It's all very Scandinavian cool and much like my place (in my dreams!). Interior design was by Fiona Denholm, who may or may not have been responsible for the Beatles and Banksy coasters artfully placed around the premises.

This is more than just a showroom; it's a showcase for Linn's vision of contemporary living, where the minimum of boxes give you both a wide feature set and high-quality sound. Every Linn DS component has the same features; it's just the audio quality that improves as you move up the range. Gilad is very much of the opinion that the separates approach is a thing of the past and that networking is the future. His view is that this will soon apply to everything in the home -- the dishwasher, the heating system, the lighting and naturally the home-entertainment system. Linn's latest DSM units like the Sneaky, released in April, have multiple HDMI inputs, so that you can route your TV sound through a decent audio system rather than the tiny rear-mounted speakers of flat-screen TVs. It makes a lot of sense and ultimately should make good-quality home entertainment easier to use and enjoy. The latest addition to the Linn range is a speaker that embodies the fewer-boxes concept. The Akubarik is an active floorstander that incorporates six channels of amplification in a module that blends into the back of the cabinet. The name, as you might surmise, indicates the use of isobaric loading of the bass drivers, which are situated at the bottom and fire downwards onto a machined-aluminum base. The magnet for the lower driver is actually concealed within the base. Unlike with the original Linn Isobarik, the drivers here are face to face rather than one behind the other. Apparently that is not the best way to do it, but it was chosen because of the front-firing nature of the bass drivers. Having your bass drivers front to front or back to back is a rather better approach. Apparently by placing the basket and its magnet at the bottom of the speaker you can arrange them optimally. I got to hear a comparison between an actively driven version of the existing Akurate 242 and the Akubarik, and the new model not only looks better and takes up considerably less room than ten channels of amplification, crossovers and loudspeaker cabinets it also sounds considerably better. There are various reasons for this, but reducing the distance between power amp and drive unit to under a foot has got to be one of the more significant ones. The other bonus is that because Linn doesn't have to house multiple channels of amplification and crossovers, the overall cost of the Akubarik is less than that of the separates alternative, some four or five thousand pounds less. The Akubarik costs £15,600/pair, so it won't be an impulse purchase for most, but if you are looking for a very capable and aesthetically pleasing loudspeaker that can produce full-bandwidth, high-resolution musical entertainment, it's a contender for your budget. Linn is also a player in the high-resolution download game. It has been releasing its own Studio Master recordings as 24-bit FLAC files for some time and has a recording engineer in the redoubtable Phil Hobbs who spends most of his time making live acoustic recordings in venues across Britain. Linn is also encouraging other labels to join the high-res cause, offering them its broad knowledge base in an attempt to extend the range of material that is available. Few labels outside the audiophile sphere have the ability to bring a genuine 24-bit/96kHz FLAC to the download market, but as Gilad points out, it's an opportunity for the end user to hear sound that is as real as that encountered in the studio, a pretty exciting concept even if you're not into hi-fi. Gilad stated that as there is unequivocally no difference in sound quality between FLAC and an uncompressed file format such as WAV or AIFF. Linn advocates FLAC not only for its proven audio performance but also because it is an open standard with good tagging functionality making it easier to organize your digital music collection, so all of Linn's Studio Masters are offered in FLAC. And given the results that Linn was able to demonstrate in its demo rooms, FLAC is clearly very capable with streamers of the quality that the company makes.

The factory’s ground floor is where the nitty-gritty of manufacturing goes on. Linn creates a lot of its own metalwork, machining and folding the casework for the DS and DSM units prior to powder-coating them. Linn also machines aluminum castings that are made out of house, but the most elaborate casework, found on the flagship Klimax range, is cast in California, where a vertical casting process is used to get maximum consistency of finish. These units are machined in Glasgow at Castle Precision Engineering, the company set up by Ivor Tiefenbrun's father and run by his brother, Marcus.

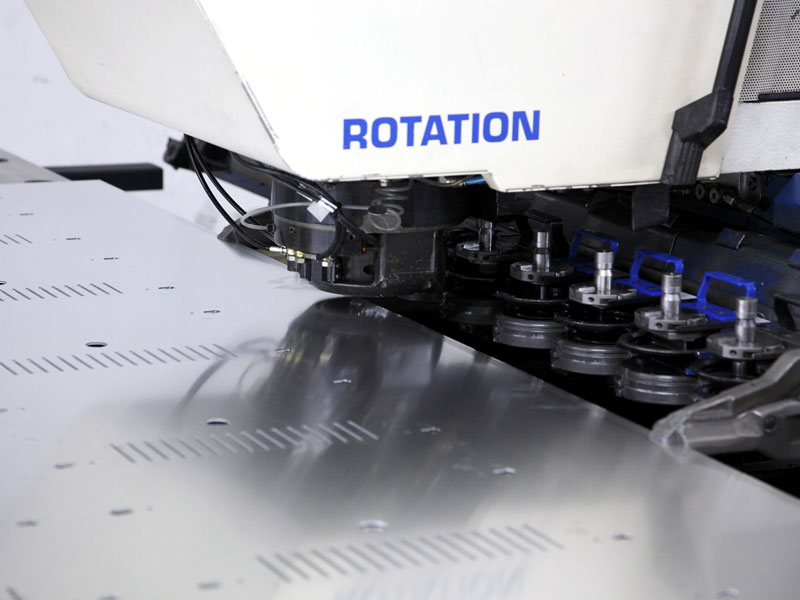

Linn builds its own circuit boards in a number of substantial SMT (surface mount technology) machines that are fed by reels of components that look like ribbons. Each stage is carefully monitored both visually by the people working and by an optical scanner that uses the reflections from misplaced solder to pick out potential problems. I particularly liked the aluminum laser-etched stencil boards that are used as templates prior to component placement. They have something of Gerhard Richter (the artist/composer) about their apparent random precision.

More conventional PCB construction goes on in the assembly area where discrete parts are manually placed prior to flow soldering. The latter involves passing the board over a running wall of solder at an angle of around 20 degrees. The solder migrates up the component legs and into the board, forming a cone without being spread on the underside of the PCB. It requires a fair degree of precision, but it is a relatively low-tech solution by Linn's standards.

When the Linn factory opened in 1987, it made an impression across the UK because of its automated stock-management system. Now that such things are more common, not much is said about the portals into the unlit warehouse where operators put orders onto pallets from products picked by machines. The AGV (automatic guided vehicle) is still quite novel, basically a small vehicle with a big bounce shield delivering parts for construction in the assembly area. It follows a specific track that you are encouraged to avoid, as the robot itself is electric and thus pretty quiet.

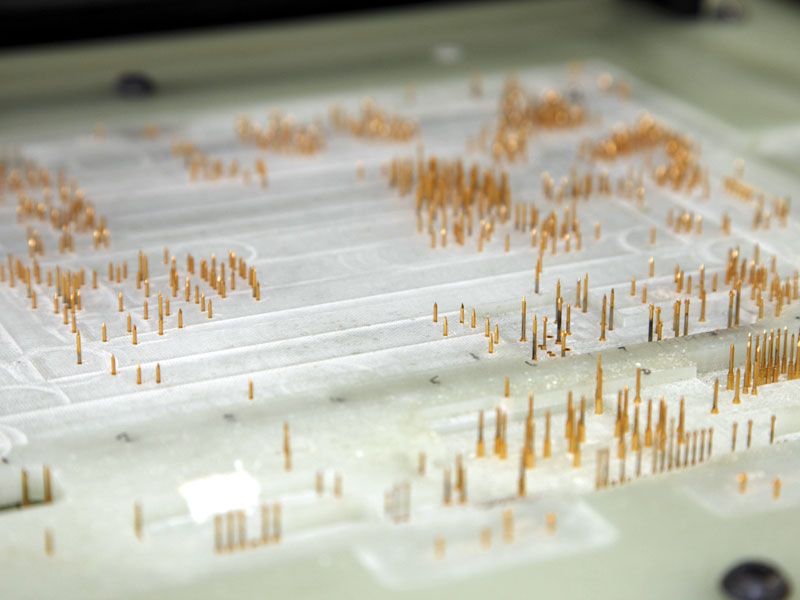

One thing I’d not previously encountered was the "bed o’ nails" test cartridges. These are cases that connect to a computer and have hundreds of tiny points that contact a circuit board in specific spots to allow multiple tests to be carried out at high speed. Each PCB requires its own cartridge, so there are hundreds of those too.

It takes Linn’s people an hour to build and test a Majik 4100 four-channel power amp and three hours to produce a pair of Akubarik Aktiv loudspeakers, so the process must be well organized. Linn recently installed a vertical CNC machine to produce a higher quality of finish on castings. This was producing Akubarik plinths when I was there, but the presence of LP12 platters in the area suggests it has other uses. Back at Linn Home, Gilad told me about how Linn Records has been talking to major labels about getting higher-quality downloads into the market. They have a deal with Universal, which I notice has resulted in Gregory Porter’s cracking new album being made available at 24-bit/96kHz resolution, and are talking to Warners, so the range of high-quality downloads is clearly on the up. One lever that has been used to convince these organizations that the small high-res market is worthwhile is that quality is really all the industry has left to sell. With Apple dominant in the MP3 market and taking the lion’s share of the profits as a result, there are few other ways to capitalize on musical assets. Perhaps surprising is the paucity of vinyl available from Linn Records, but it clearly has its sights set on networking. While you can plug an LP12 into a Linn DSM and have its output put on the network, it can’t flip sides for you.

In the listening room, production design engineer David Williamson (above) has been the LP12’s "parent" over the last seven years. He showed how the Akiva cartridge had evolved into the recently launched Kandid MC over two years in R&D. First the windings were changed, then the screw for the front pole piece was changed from metal to plastic to reduce weight and smooth out flux. A threaded aluminum chassis was tried, but steel inserts gave a stronger bond to the headshell. The three-point fixing was retained from Akiva. The angle of the cantilever was also changed from 23 to 20 degrees so that the stylus is at the correct angle to the record surface when it's actually doing its job. Other changes included removing the body, which leaves the cartridge nude, and not anodizing black, both of which reduced mass from 7.4 to 5.7 grams. The cartridge is made in Japan for Linn, but all the design work was done in Glasgow. I was also introduced to the Sneaky DSM, the latest and least expensive streamer in Linn’s range. It includes all of the features of the top model. Linn’s enthusiasm for digital streaming is based on the various advantages of the system, which it first introduced with the Klimax in 2007. These include having a "quiet box" without a spinning disc and the associated motors inside, and the fact that pulling the data from a drive or computer ensures that clocking remains accurate. The Klimax introduced gapless playback for the first time in UPnP, meaning that the playlist is stored in the player, not the control point (iPad, etc.). Apparently it took two years for Linn’s engineers to develop the DS platform, which seems pretty fast given the amount of difficulty some companies continue to have in this area.

Needless to say, Linn has an impressive operation. It appears to be the best-organized manufacturing facility in the UK. This fact, combined with the clear vision Linn has for the future of home entertainment, should ensure that the next forty years are as successful as the last. |