East Meets West Coast

’ve visited monks in Himalayan temples, but for some reason I have not until recently made the half-hour journey to the Piedmont, California, lair of the Mad Monk of Shun Mook, Bill Ying. Set high in the hills of the San Francisco Bay, Bill’s home sits above the fogbank that often blankets San Francisco. Nice weather, but the air was not so thin as to account for all the storied magic; not quite the Himalayas, but high enough.

Bill Ying amidst his record collection. Bill earned his sobriquet in the mid-1990s because of the sheer audacity of his ideas incorporated in a handful of Shun Mook system-tuning devices, including Mpingo Discs, Diamond Resonators and his company's LP Record Clamp, all made from either the heart or root of the African ebony tree.

A visit to Bill’s listening room, however, establishes that these controversial tuning devices are just the start of his explorations. A week earlier, I had visited Thomas Edison’s "invention factory" at Greenfield Village in Michigan, and Bill’s home shared much with Edison’s workplace. Beyond the obvious differences like the patent plaques decorating the walls, there was a plethora of novel and interesting applications of old technology. Clearly Bill loves all things Western Electric, starting off with his electronics. His preamp and amp are from small production runs of Western Electric replicas manufactured by a Chinese audio buff and incorporating vintage Western Electric tubes.

More unusual is his choice of wire used for speaker cables, interconnects and power cords. Bill makes all his cables from vintage cloth-wrapped wire sold off decades ago by Western Electric and acquired in bulk by a Japanese audiophile who is now Bill’s source. Bill contends that the wire has superior qualities due to the aging of the vintage copper and the superiority of the natural-fiber sheath, which he believes is a superior insulator to Teflon or any similar material. He has the wire cut to set lengths, and he then files the ends down, listens to the wires in his system, files the ends some more and listens again, repeating the process until he is satisfied with the sound. His method of cable connection is similarly unique. Lightness of touch is the key. He uses no bulky connectors or clamped-on connections. Instead, he practically lets the weight of the wire establish contact with the component. Stranded cable is used for the signal, with a solid core return path and another wire wrapped loosely around the two conductors, which holds the package together and at the same time is a drain for EMI.

As Bill concedes, these are not cables for audiophiles trying to impress friends with expensive-looking wire, and he matches this simplicity with his dedicated power lines. I thought I was falling through the rabbit hole when he answered my query about his house wiring. He had the wiring throughout his 80-year-old home modernized, except for the listening room, where he maintained the old knob-and-tube wiring. Anyone who has done demolition of old walls knows that knob-and-tube wiring is wrapped in fabric, so it more closely resembles the Western Electric wire Bill uses throughout his audio system. These vintage circuits did not include a ground wire, so a dedicated ground circuit was added, draining to a custom copper earth stake. Bill installed copper tubing rather than the usual copper-plated steel ground stake. The tubing is far more expensive and more difficult to install. As unusual as the choice of materials seems to be, it pales in comparison to the presentation. Interconnects and cables appear to have taken over the open space behind the speakers. It's a scene demanding its own musical score, and my first choice would be The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Wires are strung in a spider’s-web array behind the speakers, and when Bill ventured in that territory to demonstrate the impact on the sound of moving one of his room-tuning devices, he conceded that one misstep could require hours of testing to retune the room with a meticulously placed system of wires and pulleys.

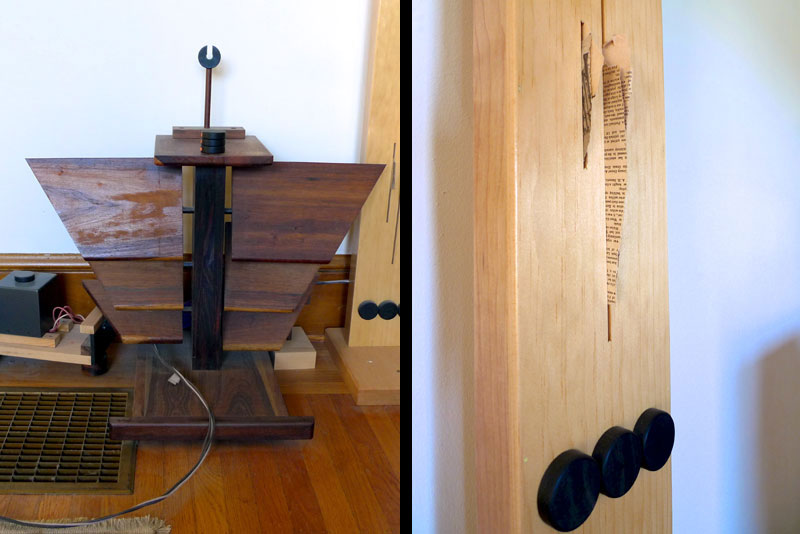

Along the walls are his room-tuning towers. Each tower is made up of several chambers. Mpingo Discs are attached to the outside, and there are slit openings into which Bill inserts newsprint, experimenting to find the right room-tuning effect. He claims to have compared the sonic virtues of various types of newspaper and discovered that the old stuff works best. He found a source for Civil War-era newspaper and uses that to fill the commercial versions of his tuning towers. (Only his consumer towers have slits into which slips of paper are inserted. Commercial versions have the newspaper hidden inside the chambers permanently.) He also has Civil War-era newspaper attached to the face of his fireplace. He has used these towers in commercial projects, including concert halls and a church in Korea. Those spaces are professionally finished and bear none of the mad-scientist, Back to the Future décor of his listening room. The listening room is actually a woodworker’s dream. In addition to hardwood floors, Bill has constructed various ebony support devices to hold his components and be used as cable guides. His room is filled with (I lost count) many student violins and a bass viola, all for purposes of tuning. A giant ebony log commands the foreground. All this adds up to an extremely good-sounding system. Bill's analog rig consists of an Oracle Delphi Mk IV turntable with a special cobalt-amorphous-core transformer in its power supply, an SAEC 407/23 tonearm with Shun Mook ebony headshell, and a Shun Mook Reference moving-coil cartridge (with engine built by Zyx in Japan). His phono stage is an Audio Research Reference Phono. His replica Western Electric preamp and amps both feature Shun Mook modifications. His Shun Mook Bella Voce Reference speakers have a sunburst high-gloss lacquer finish. Bill's CD player is a very old Pioneer PD-203 that he has heavily modified, including making it into a top-loader. He didn't seem inclined to play any CDs, so I didn't hear any. Given the fact that the most recently produced component in the system is the Audio Research phono stage, I was truly surprised at how magical it all sounded. The speakers were coherent from top to bottom and had better bass than their size promised. However, the system's real strong suit was its huge soundstage. With large-scale orchestral music, the depth and width were extraordinary. Bill made a convincing demonstration that his tuning devices made a big contribution to that end. With a few manipulations, I had no difficulty hearing the changes in the soundstage.

Despite the Mad Monk’s reputation, which is in no way dispelled by his unique tuning ideas, Bill is an engaging and normal guy who really loves music and prizes his record collection. Indeed, Shun Mook is really a hobby meant to help him enjoy his passion for music. His first love is jazz, and he has amassed a stash of original Blue Note LPs, many of which he played for me. After many hours of listening to favorite records, Bill

sent me home with a handful of Mpingo Discs to play with. I'll be having him over to

compare jazz rarities, but first my head will need to stop spinning. |