B&W:

Speaker Building the UK Way

Today the factory employs 320 people who make and sell loudspeakers as well as run logistics for a company whose core business is still hi-fi. B&W has a London office where most of the marketing is handled and an R&D department in the nearby town of Steyning, where the really interesting stuff goes on -- so interesting that it is now off limits to journalists. I’ve been to the Steyning facility in the past and seen the extensive facilities for investigating how loudspeakers work and what can be done to improve them. The facility has anechoic chambers, numerous devices for measurement, CAD modeling -- everything you need to develop a state-of-the-art loudspeaker. Bowers & Wilkins has the best facility in the country, possibly in the world, and some of the brightest talents in the industry -- people who get to listen to different brands of capacitor all day for their sins. I’m not sure what’s brewing at the moment, but I am told that there will be new product announcements toward the end of of this month. Steyning is where all the listening is done -- in a room that takes a bit of getting used to but is undoubtedly analytical and capable of remarkable results, despite the absence of a serious turntable!

For this piece, however, I visited Dale Road, Worthing, where the 800 Diamond series is built from the ground up and parts are made for 600-series models, these sent out to the company’s Chinese facility in Zhuhai. My tour of the factory started in the warehouse, where 52.5'-high racking is managed by chaps who have to train in abseiling as well as fork-lift driving. By British-audio-industry standards, this is a big storage space.

Testing and measurement are in Bowers & Wilkins’ blood, so it wasn’t surprising to be shown the environmental testing facility where components are exposed to extremes of temperature, humidity and UV light in an effort to build a more robust and longer-lasting speaker. Every time a new component comes online or a supplier is changed the parts are given rigorous testing. One machine simulates the equivalent of a year’s exposure to UV, a process that takes 1001 hours for some reason. Another is a salt-spray bath for weather-proofed monitors like the AM1, which is also found on top of the building. There is a pair outside at Zhuhai too, where conditions are very different. The most lively test bench was pulling on the cords of C5 earbuds to test their durability.

In the next room quality-assurance manager Dave Naylor (shown above) tests P3 headphones with a motorized force gauge to measure how many bends of the headband it can take before resistance in the metalwork goes down. He also tests cones and explained how a reinforcing ring had to be added to the edge of the Rohacell foam-cored driver in the DB1 subwoofer to stop it from delaminating. As production-support engineer Peter Paice demonstrated to me, the cone is now strong enough to support a man, if that man has a good sense of balance. In the same room, Peter Jeffery, senior metrology engineer, uses a number of tools to check that supplied parts are up to spec. Some parts are unusually finely toleranced; the surround on the Diamond tweeter, for instance, has a tolerance of +/-0.1mm, which is quite a challenge to achieve for a rubber part. He uses a Shadowgraph machine to measure the thickness of such parts as well as a three-axis measuring machine with a ruby-tipped, touch-sensitive probe that can measure in three dimensions and sits on a massive granite base -- a fine equipment stand that would make. When I visited 800 Diamond-series tweeter pole pieces were being checked for bolt positioning because the company had been having difficulty with supplies.

The distinctive head on the 800 and 802 models is molded in Marlan, a composite material, by a company in Holland, but all the finishing and paintwork are done in-house. A black powder is used to show imperfections in the finish so that they can be eliminated prior to painting. The gloss-black finish has proved to be the most popular option in the 800 Diamond series and it’s also the most difficult to produce. Apparently when the 800 Diamond range was launched, 95% of orders were for this finish. It requires five base coats and as many top coats, because the final paint finish has an unavoidable orange-peel effect and the only way to eliminate it is to rub, or "flat," the paintwork down with ever-finer grades of glass paper before polishing it back to a gloss finish. This translates to twice the labor that it takes to produce a lacquered, wood-veneer finish and there is no price premium. A polish used on cars achieves the extraordinary luster -- that and two hours of polishing on the HDM1 center-channel speaker, which is the smallest 800-series model. A Nautilus, on the other hand, takes a day to polish, and all paintwork needs to be left for three days to dry. In the assembly area the smallest Diamond model, the 805, was in production, each cabinet laminated, formed, machined and assembled using urea glue that can be detected with UV light, which means all traces of it can be removed prior to lacquering. The Matrix internal bracing is assembled at the same time the wiring harness is added, because it’s too cramped to thread cables through once the bracing is inside the cabinet. This is done in the cabinet-assembly area, where high fans spray water droplets into the air in order to keep the humidity at the right level and stop the laminated wood from cracking.

While some of the cabinets are spray-painted by hand, most are painted by a robot on a fairly long automated line that includes a heated drying area. This has increased turnaround for the larger speakers quite dramatically by removing what was a bottleneck in production.

Upstairs is the voice-coil-winding department run by Tony Wouldham. Because of high humidity in China, his team produces voice coils for speakers that are assembled in the Zhuhai facility. It’s the resin coating that is sensitive to atmospheric conditions, and this is used on the coil wire as well as the Kapton former it sits on. The formers for 800-series drivers have glass fibers, which give a better stiffness-to-weight ratio in larger diameters. I was shown the double-spider arrangement for the bass drivers on an 800 Diamond, which looks and feels extremely stiff.

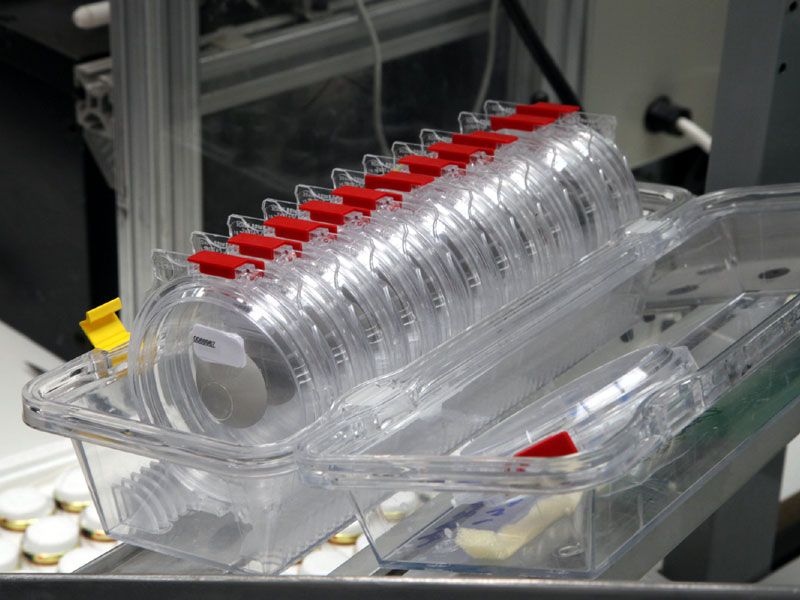

The only tweeters made in Worthing are the diamond-domes for the 800 Diamond series -- a tray of domes that had not passed QC was on hand, so I could handle them. You would not believe how fragile they are. I’ve been doubly cautious when going near the 802 Diamonds I use as a reference ever since.

The diamond is synthetically grown by a process called CVD (chemical vapor deposition) by a division of De Beers in the UK. Being carbon, each dome is naturally dark gray in color, the silver finish achieved with a platinum coating. Tweeter production is managed by Jeanie Bradshaw, who took me through the process of gluing the domes onto coils and then incorporating them into housings with six magnets that are finally fitted into the familiar tapered-tube casework you see on the 800 Diamond range. B&W originally outsourced production of the Rohacell cores for its drivers, but it has brought this in-house in order to have full control. The yellow Kevlar cones that you see on many Bowers & Wilkins midranges and woofers are stretched into shape by warming them and pressing them into a form three times. The secret of building a consistently good-sounding cone is apparently in the resin that bonds the fibers together. For final speaker assembly, the drive units are barcode matched to their particular cabinets so that the company can trace the origin of rogue parts, which sometimes appear on the international market.

Given that Dale Road, Worthing, only

represents 800-series manufacturing, it’s an impressive place, bigger, I suspect,

than any other facility in the country. Bowers & Wilkins goes to extreme lengths to

ensure quality and consistency in its products, and despite the inevitable high costs

involved, the 800 Diamond series represents remarkable value in the context of high-end

loudspeakers. The people on the factory floor are clearly dedicated to producing top-notch

speakers, and the fact that they contribute key parts to the more affordable ranges built

in the Far East indicates that "Made in Great Britain" still has something to

offer in these challenging times. |