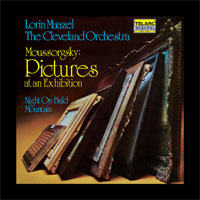

Moussorgsky • Pictures at an Exhibition Cleveland Orchestra, Lorin Maazel conducting

A second reason for the nostalgia was that, when I purchased this record, I was in graduate school and just beginning to build a record collection. In the bins of my local record store were recordings from a new label, Telarc, with those bright yellow logos introducing “Telarc Digital” and “Soundstream Digital Recording System” on the album jackets. Although I had no real idea what it all meant, the idea of digitally recorded music was new and exciting. Looking back, I can relate to the thrill of late-1950s record buyers at seeing the word “Stereo” in bold type on their new purchases, eschewing old-fashioned monaural recordings in favor of the new stereo releases. Founded in 1977 by Jack Renner and Robert Woods, Telarc was an early adopter of the Soundstream Digital Recording System. They had heard a Soundstream recording in 1976 and initiated discussions with Thomas Stockham, founder of Soundstream, which resulted in some improvements to the recording system and a long-term musical relationship. Telarc recordings rapidly became a staple for audiophiles through their recordings of the Cleveland, Atlanta and St. Louis orchestras. Many audiophiles will remember Telarc’s recordings of organist Michael Murray that challenged their system’s low-end response. Another bonus was reading Telarc’s record jackets and their listing of microphones, mixing boards, amplifiers and speakers used in each recording session. Stockham’s recording system used Honeywell 5600e instrumentation tape drives, running at 30 inches per second, across custom eighteen-track recording and playback heads. This allowed the Soundstream system to include time codes and up to eight channels of stereo. This new recorder had impressive specifications for the time: 16-bit format with 50,000 samples per second, immeasurable wow and flutter, low distortion and a 90dB dynamic range. It’s helpful to remember that this was six years before compact discs debuted. Soundstream provided their recording services to labels such as RCA, Philips, Angel, CBS, and others, but it was the Telarc collaboration that brought the most attention from audiophiles. Craft Recordings has been lauded for their reproduction of original LP jackets. One aspect that doesn’t get mentioned enough is their promotional restraint. There are only two hints that it is not an original pressing. The first is the cellophane wrapper, which has a small sticker crediting the mastering and pressing production teams and a short description of why this Telarc recording is important. On that sticker, we learn that Paul Blakemore was in charge of mastering this reissue, using the original Soundstream tapes as the source. Lacquers were cut by Ryan Smith of Sterling Sound and Optimal did the pressing on 180-gram vinyl. Once the outer wrapper is removed, the only other clue that this is a reissue (aside from slightly brighter front cover artwork) is that a new Craft Recordings catalogue number, which replaces the original Telarc number. Following a well-played, but fairly standard interpretation of Night on Bald Mountain, Lorin Maazel’s version of Pictures at an Exhibition emphasizes melodic line versus sheer impact of the big moments. Listeners are not shortchanged as the big, bold movements are still impactful, but Maazel chooses slightly quicker tempos in most movements, so the melodic lines of the “Promenade” interludes are hymn-like. For contrast, Reiner’s recording of Pictures with the Chicago Symphony is darker and more forceful; it looks for moments of stress, anguish or even terror. Maazel still manages to find drama, but tempers the contrasting movements with a gentler, singing style. One other stylistic feature is Maazel’s holding of notes at the end of phrases or inserting a small pause before moving to the next phrase. It gives extra interest and shape to melodic lines, an interpretation I’ve not heard in other recordings. The Cleveland Orchestra's strings are especially strong on this recording, with excellent unison intonation. Their octave work in the introduction to “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle” is particularly good. Mussorgsky’s writing and Ravel’s arranging for low brass are played with gusto and a good measure of growl, while the upper-brass performance is effortless, even at the end of “Great Gate of Kiev.” The recording captures all the power and depth of bass-drum rolls, timpani, and the contrabassoon. With this reissue, Craft Recordings manages to improve upon the original in three important ways. First, the reissue is cut at a slightly reduced level, and whether it was this or simply a better pressing than the original, the loudest sections of the recording are easier to track. It is most noticeable on those massive brass chords and tam-tam strikes at the end of “Great Gate of Kiev,” which are in the crowded inner grooves at the end of side 2. The reissue is significantly better at this than the original. Second, there is overall improvement in the clarity of massed strings. On the original recording, the string sound is smooth, but somewhat glassy. The reissue renders strings with clarity and more sound of vibration by rosin on the bow. A visiting musician friend commented that the clarity let her hear the famous blend and balance of the brass and woodwind choirs. A pleasant surprise comes in the form of the tuba solo in “Bydlo.” The original recording sounds generic, but I now hear the subtle vibrato and shaping of the solo line, enhancing the somber beauty Mussorgsky/Ravel intended. Finally, the muted trumpet solo in “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle” is oddly distant in the original. A muted trumpet sounds loud and aggressive, projecting over the orchestra in any concert hall. The reissue puts Adelstein’s solo in its proper balance. It is also easier to hear that the solo was not a muted piccolo trumpet, as is frequently used today, but a muted C trumpet. Craft’s accomplishment with this recording becomes

the gold standard for all future Telarc reissues. Fortissimo musical sections are more

easily tracked by my cartridge and with greater clarity and less distortion than from the

1979 original pressing. There is noticeably increased resolution, which allows individual

instruments to be heard during dense scoring. Finally, any remixing or rebalancing of the

original tracks are minimal and yield an improved musical experience. My wish list for

future Telarc reissues would include some of the fine St. Louis and Atlanta orchestral

releases as well as the Frederick Fennel wind-band titles. |

had a strong feeling of nostalgia while opening the

shipping box from Craft Recordings and seeing this Telarc LP. During my trumpet lessons in

college, the opening trumpet solo, “Promenade,” from Pictures at an

Exhibition, was the first orchestral excerpt I studied. I would go to the library and

listen to the Chicago Symphony’s great principal trumpeter, Bud Herseth, and try to

emulate his version of the solo. When Telarc released this recording of Pictures at an

Exhibition in 1979, I was eager to hear another legendary trumpeter, Cleveland

Orchestra’s Bernard Adelstein, and his version of this famous trumpet excerpt.

had a strong feeling of nostalgia while opening the

shipping box from Craft Recordings and seeing this Telarc LP. During my trumpet lessons in

college, the opening trumpet solo, “Promenade,” from Pictures at an

Exhibition, was the first orchestral excerpt I studied. I would go to the library and

listen to the Chicago Symphony’s great principal trumpeter, Bud Herseth, and try to

emulate his version of the solo. When Telarc released this recording of Pictures at an

Exhibition in 1979, I was eager to hear another legendary trumpeter, Cleveland

Orchestra’s Bernard Adelstein, and his version of this famous trumpet excerpt.