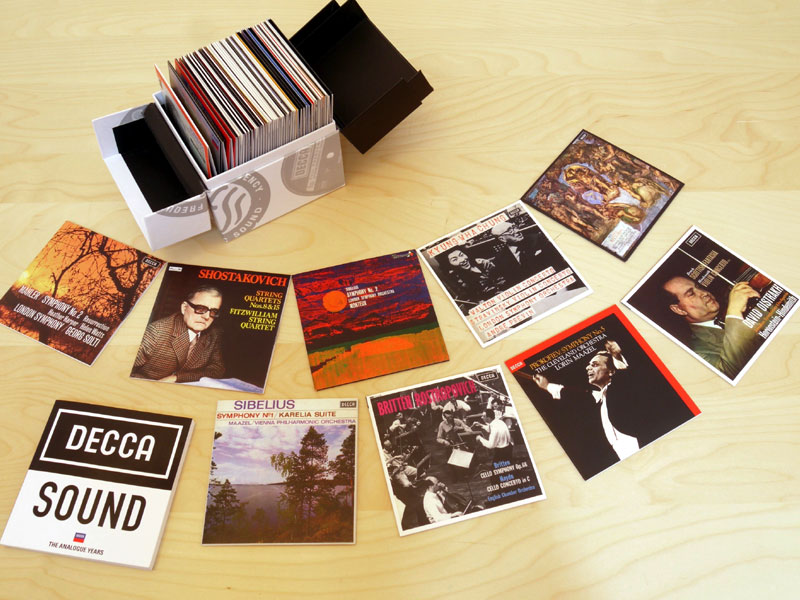

The Decca Sound - The Analogue Years Universal/Decca 478 5437

The original Decca Sound box, in its distinctive red-and-blue chest, was a comprehensive history of the Decca classical labels, from the mono days of FFRR, through the early stereo days of FFSS, Argo and L'Oiseau-Lyre, right up to the latest CD issues. There were more than a few real gems in amongst those 50 discs, but there were also a few landmark titles, like Decca’s first digital release (Biskovsky/VPO New Year’s Day Concert In Vienna) and The Three Tenors, choices that reflected the commercial rather than artistic high points of the label. Still, at less than $3 a disc, the set as a whole was a massive musical bargain. Now comes the second Decca Sound box -- The Analogue Years -- and if the first set leaned toward the history student, this is one for the audiophile and the student of recording, its techniques and evolution. Few classical collectors would argue that the Decca catalogue in the '60s and '70s represented something of a golden age, but to start with at least that reflects the quality of the recordings as much as the quality of the artists roster. Great recordings capturing emerging talents was a recipe for fantastic records and musical documents that have withstood the test of time. I’m not going to laboriously run through the repertoire here -- life’s too short and you can just search Amazon for the complete list -- but suffice to say, it’s both extensive and musically and sonically rewarding. With 54 discs to choose from, there shouldn’t be many potential purchasers questioning the value here, but that’s only half the story. Of those 54 discs, 36 have considerable additional material added, reflecting the shorter run time of the original LPs. Tot up the extra tracks and you are probably looking at the equivalent of 75 LPs, especially if you consider that there are two operas and several longer works here that originally constituted two- or three-disc sets. Nor are the extra offerings mere filler. So, Britten’s 1972 Snape recording of scenes from Schumann’s Faust is paired with a previously unreleased 1963 performance of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40, captured in Kingsway Hall by the legendary Kenneth Wilkinson. And therein lies the clue. Despite the sheer wealth of recorded music contained in this box, the place to start is with the booklet and the essay that lays out, clearly and concisely, the stages and evolutions in the Decca recording technique, the equipment used and the personalities that shaped the recordings. As Arthur Haddy was fond of commenting, it was the people who made the recordings, not the equipment they used -- although that also clearly played a part -- that made Decca what it is. The recordings that constitute this box have been selected with a clear logic, reflecting both the evolution of the recording chain and also the work of legendary producers like Culshaw and Minshull and engineers such as Wallace, Wilkinson, Dunkerley, Parry, Goodall and Tryggvason, in all of Decca’s most popular recording venues. The range of recorded perspectives is remarkable, and for once we know who was responsible and why they got the results they did, a somewhat ironic bonus of invaluable information for those still working on their collections of SXL2000- and '6000-series LPs.

The musical choices here show some imagination too, complementing both other discs within this box as well as the recordings from the first one. So, if we take Sibelius as an example, we are treated to the fantastic Maazel/VPO reading of Symphony No. 1 and the Karelia Suite, paired with the No. 4 as an extra. That gives you the chance to hear the work of Gordon Parry, directed by the great John Culshaw or Eric Smith, in the Sofiensaal, Vienna, the recordings separated by five years (’63 and ’68). Together the program adds up to two complete LPs and a running time of over 82 minutes. But that’s not all. By way of contrast, you also get another disc containing the famous Monteux/LSO reading of Symphony No. 2 (paired here with Dvorak’s Seventh) recorded by the Culshaw/Wilkinson team in 1958 at Kingsway Hall, for another 81-minute musical extravaganza. Finally, there’s a later (1971) disc of Horst Stein and the OSR -- Decca’s first "stereo" orchestra -- recorded in the Victoria Hall, Geneva, featuring Pelleas et Mellisande and The Tempest, with En Saga and Pohjola’s Daughter as bonus tracks. Now, look in box one and you’ll find Ashkenazy conducting the Philharmonia, recorded DDD at Walthamstow Assembly Hall in 1984 by Stanley Goodall. Throw in the inclusion in box two of Decca’s earliest stereo recordings, a mixed Russian repertoire performed by Ansermet and the OSR (included in both stereo and mono versions) captured at the Victoria Hall by Roy Wallace in 1954, and you can see how the tracks in not just the Analogue box but the original box as wel, fit together to create extended threads that lead you through the fabric of classical music as well as the history of Decca, its recordings and the changes in technology and styles of performance. Don’t despair if Sibelius isn’t the first name to trip off your tongue. Box two contains the (in)famous Mehta/LAPO TAS-listed Planets, recorded in 1970, while box one includes Karajan and the VPO performing the same work, recorded in the Sofiensaal in 1961 by Culshaw and Parry. Likewise, box one includes Curzon playing the Mozart Piano Concerto No. 27 (K.595) with Britten and the ECO, recorded at Snape in 1970 by the Minshull/Wilkinson pairing, while box two includes Curzon’s 1964 reading of the same work, recorded in the Sofiensaal by Gordon Parry, with Szell and the VPO. It’s like a game of wheels within wheels within wheels. What I’ve described is just the tip of the iceberg. The opportunities to compare and contrast seem endless, each disc leading to another: Different conductors, orchestras, soloists and venues create an infinitely varied collage -- and that’s before you even consider the dates of the recordings and the personnel and technology involved. If that all seems a little academic, don’t worry. There are plenty of Decca’s greatest recordings included here: from Karajan’s Othello to Serafin’s La Boheme, to legendary recordings by Kyung-Wha Chung and Radu Lupu, Solti, Abbado and Maazel. There’s La Fille Mal Garde and the Oistrakh/LSO, Bruch Scottish Fantasia, while the extra tracks add further surprises to the staple fare. How do the discs themselves compare to full-price issues? Perhaps the most interesting comparison here is the box-two version of the Mehta Planets to the previous XRCD reissue. Listening side by side, you’ll need to match levels carefully (another smartphone app that’s too useful to miss) as the Decca disc is encoded at a lower level than the XRCD, but once you get the volume set you’ll discover that the budget CD actually outperforms the audiophile issue. Crisper, cleaner and more transparent, it has more energy, more texture and greater dynamic range than the XRCD, which sounds rounded, congested and muddy in comparison. The sense of multiple instruments, of bowing and the individual tonalities of the brass and woodwinds, is far better on the Decca, but the real clincher in this case is that all that clarity and immediacy add up to a more vivid, dramatic and compelling performance -- all the things this recording is known for. The XRCD might not be the last word as regards this recording, but it does demonstrate that the Decca disc is no slouch, while the inclusion of the Saint-SaŽns "Organ Symphony" is, quite literally a bonus. No, the new CD doesn’t match the original LP for staging or acoustic coherence, at least not if you have a Decca curve in your phono stage. However, play the original issue at RIAA and the CD gets an awful lot closer. The Speakers Corner reissue goes a long way to restoring the quality gap, but that’s another story. The bottom line (as if one were needed) is that The Analogue Years contains great transfers of great recordings of some great musical performances. Given the price, this should be a no-brainer, especially if you already own The Decca Sound set. The two work in tandem, and the fact that the whole is even greater than the considerable sum of the parts stands testimony to just how cleverly this project has been managed. Whether your first love was LP or your current tastes run

to file replay, these recordings are essential listening, and The Analogue Years

is both the most affordable and the most interesting way to access them. |