American Recording Premieres of Tchaikovsky Symphonies: Still Engaging After All These Years

bout 75 years ago, Victor Records, which had not yet begun calling itself RCA Victor, was without question the dominant American label for classical music. Victor had on its roster the Philadelphia Orchestra under both Leopold Stokowski and Eugene Ormandy, the Boston Symphony under Serge Koussevitzky, the Boston Pops under Arthur Fiedler, the NBC Symphony under both Arturo Toscanini and Stokowski, the Chicago Symphony under Frederick Stock -- in addition to material from EMI’s "His Master’s Voice" label and other European sources. By 1941, the newly ambitious Columbia Masterworks, which had its own EMI source, English Columbia, had already taken the post-Toscanini New York Philharmonic, under John Barbirolli, from Victor, and was recording that orchestra under Bruno Walter and Igor Stravinsky as well. It was about to acquire the Philadelphians, the orchestra that had been Victor’s living laboratory in developing new recording techniques over the years. Columbia had also signed Dimitri Mitropoulos and the Minneapolis SO, the orchestra which, only a few years earlier, under Ormandy, made recording history in a number of ways, while putting Ormandy in position to succeed Stokowski in Philadelphia. At the same time, however, Victor showed great imaginativeness in signing a number of nominally second-string orchestras (which had some well-known and much-admired players on their personnel lists), under conductors both renowned and lesser known, and recording them in fascinating repertory that had been more or less neglected but was liberated from that status virtually overnight as the listening public enjoyed discovering it. The revered Pierre Monteux began a significant series with the San Francisco SO, which had made a few recordings under his predecessor Alfred Hertz (also for Victor), when Ossip Gabrilowitsch and the Detroit SO also made a few for the same label and the St. Louis SO, under Rudolph Ganz and then Vladimir Golschmann, recorded briefly for both Victor and Columbia. The San Franciscans immediately attained a new status with Monteux’s authoritative readings of music with which he was particularly identified and a generous helping of material new to most listeners. Fabien Sevitzky, a nephew of Boston’s Koussevitzky, made a strong impression with his fine-sounding Indianapolis SO in similarly authoritative readings of little-known Russian music (and little-known Haydn) and immediately attained a new status, while Golschmann, in St. Louis, was similarly persuasive in works of Sibelius, Schoenberg, Milhaud et al.

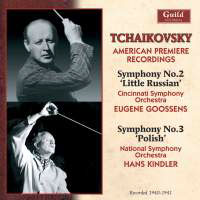

Stravinsky did not record any symphonies but his own. The Goossens and Kindler performances on the new Guild CD are of huge significance in the Tchaikovsky discography. They were in fact part of Victor’s imaginative and handsomely achieved coverage of all four of the lesser-known completed symphonies by one of the most beloved of all composers. All four of these were premiere recordings of the respective works in their complete form, and might have been assured welcomes simply for filling those gaps, but they remain valuable because they did a good deal more than that. As a symphonist, Tchaikovsky had been represented in concerts and recordings almost entirely by the last three of his six numbered works in this form, which were then, and remain today, among the most widely known and admired of all symphonies from any period. In addition to No.2 under Goossens and No.3 under Kindler, Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No.1 (called "Winter Daydreams") and the grand-scaled later symphony after Byron’s Manfred (to which the composer gave no number other than its opus number) were assigned to Sevitzky, whose Indianapolis team brought them off with utter conviction and all the brilliance demanded by the scores. Those demands are by no means incidental, and the persuasive Goossens performance of the Second and Kindler’s of No.3 circulated just now on Guild GHCD 2422 remain fairly definitive guides to these works in every respect. This is no surprise in the "Little Russian." Goossens, the best-known member of a very distinguished musical family of Belgian origin (the remarkable oboist Léon Goossens was his brother), deserves a wider remembrance than has been his lot. His orchestra in Cincinnati was one of the senior ensembles in our country. It was, by no means incidentally, the one with which Stokowski initiated his amazing American podium career, and Goossens’ immediate predecessor was the enormously respected Fritz Reiner, who had become music director of the Pittsburgh SO and had begun recording for Columbia. Everything about a Goossens performance seemed to shine with that elusive "inevitability of rightness," in such concerns as tempo, phrasing and balance. He was an acknowledged composer himself, and there was nothing he did not fully comprehend and master regarding the make-up and function of the modern orchestra. This particular performance remains an especially illuminating demonstration of his unfailing instincts, while demonstrating also the composer’s own judicious instincts in undertaking a thoroughgoing revision of this work some seven years after the premiere of its original version, having in the meantime introduced such masterworks as his Fourth Symphony, the ballet Swan Lake, the Violin Concerto, the First Piano Concerto and the opera Evgeny Onegin. In any event, the original version of the Second Symphony has been recorded by Geoffrey Simon and the London SO, on Chandos, and may be of interest to listeners with that sort of curiosity. The final version has been recorded many times by now, but on grounds of persuasive performance the one under Goossens has never been surpassed. The sound has been grandly surpassed in every recording of the work that originated on LP or CD, my own choice among which would be those by the London SO under Igor Markevitch, on Philips, and by Ormandy and the Philadelphians on RCA Victor.

Hans Kindler and the orchestra he founded in Washington had the measure of the Third Symphony hardly less intuitively than Goossens had that of the Second in Cincinnati. Kindler had been active as a cellist before he created the National SO, and his discography is limited to that orchestra. He was barely into his twenties when Stokowski made him principal cellist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and he gave the premiere of Bloch’s Schelomo in New York. Stokowski provided him with an opportunity to conduct, and he formed the National SO in 1931. Both of these splendid musicians understood the truly basic importance the element of charm held for Tchaikovsky throughout all his creative efforts. The word "efforts," in fact, barely fits into this reference, for charm was never the result of conscious effort on this composer’s part, but simply and indispensably part of his instinctive understanding of what composing was all about -- in a different personal character, but every bit as inborn to him as to his French contemporary Emmanuel Chabrier. It was the way such creators saw and understood life, and and it inevitably made itself felt in their work. One suspects, in fact, that one of the reasons the Third Symphony became the first one which Tchaikovsky allowed to stand without major revisions was that he relaxed his concerns about form and simply allowed that inborn charm to take charge without the slightest resistance. This is particularly evident in the curious intermezzo, headed Alla tedesca, that is the second of this work’s five movements. (No.3 is Tchaikovsky’s only five-movement symphony, also the only one in a major key, and was the first to be performed in America.) Leonard Bernstein, among others, seemed to regard this straightforward movement as something far more self-concerned than it is, adopting a tempo at which it simply could not proceed in anything like a natural flow: Kindler was mindful of its core of spontaneity -- fairly close to outright playfulness -- saving any hints of conscious sobriety, not even for the preceding movement’s introduction (marked Tempo di Marcia funebre), but for the work’s central Andante elegiaco. Tchaikovsky eventually recycled the Alla tedesca as part incidental music for a staging of Hamlet, to accompany one of the play’s lighter scenes. As for these two symphonies’ subtitles, "Little Russia" is the informal name Russians used to apply to Ukraine, and this unpretentiously engaging symphony is built partially on attractive Ukrainian folk tunes. In respect to the Third Symphony, however, it appears that the label "Polish" had nothing to do with folk tunes or any specifically Polish reference, or even with Tchaikovsky himself, who never even knew about that word’s attachment to the work: Sir August Manns, the longtime conductor of the Crystal Palace concerts in London, affixed that title six years after Tchaikovsky’s death for no better reason than that the final movement is headed Alla polacca and is more or less in the form of a polonaise. To be sure, both of these recordings show their age. At the time they were made, Victor was not doing too well in recording timpani in orchestral works. At best we were offered some indistinct, distant-sounding blurs -- not even full-blooded thuds, certainly no almost visible images of sticks hitting drumheads. (Columbia was doing better in this particular respect; compare the drum presence in that label’s recording of another Tchaikovsky piece, Marche slave, played by the Cleveland Orchestra under Artur Rodzinski, with the contemporaneous one on Victor with Fiedler and the Boston Pops, or compare Rodzinski’s Columbia recording of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, with Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra on Victor.) In general, though, Victor’s all-round orchestral sound outclassed Columbia’s in those days, with its silky strings, luminous brass, and richly realistic woodwinds. With that in mind, and with the remarkably ingratiating character of the performances themselves (and no detail is missing from the sizzle Goossens brings to the "Little Russian’s" finale), one may imagine that even listeners beyond those specific individuals who actually grew up on these recordings would find very little effort required in making the necessary allowances for the sound quality here. Once you get a few bars into either of them, you’re simply hooked, and rather awed by the thought that this sort of thing is what we used to expect in concerts and recordings way back when. The Goossens "Little Russian" was apparently the work’s premiere recording. Another British conductor, Albert Coates, actually born in Russia when his father managed a business office there, earned a fine reputation for his performances of Russian music, and in 1932 he made the earliest recording of the Third Symphony, with the London SO, for HMV (issued here by Victor), but it was severely cut, the central Andante elegiaco whittled down to about a third of its expansive full length, so Kindler’s fine recording, with only minor cuts here and there, may also qualify as the work’s actual disc premiere. This thoughtful pairing of truly historical recordings is a lovely reminder that musical content can sometimes override sonic considerations. Which is not to suggest that either of these recordings might be regarded as being indispensable, in any context -- but for more than a few collectors the pairing of them on a single CD may be definitely worthwhile, even if not indispensable, for they are valuable reminders of just when and how certain by-now-familiar parts of the orchestral repertory first began to become part of the general public’s listening activity, and reminders as well of the quite remarkable standards of performance among our supposedly second-level orchestras, and of the imaginativeness of both the musicians themselves and the American recording companies that pioneered this repertory right here at home. By now, thanks to these pioneers, all these little-known works they championed have become part of the general repertory, and are well represented by latter-day performers in the realistically brilliant recordings we expect nowadays, but several of us old-timers have willingly retained the sound-image of these performances as the ones against which we happily continue to measure all subsequent ones, on 78, on LP, in mono and stereo, on CD and beyond. And now, if Guild, or some other resourceful reissue

label, would complete this implied project by bringing us those Sevitzky/Indianapolis

recordings of Tchaikovsky’s First Symphony ("Winter Daydreams") and Manfred

-- both of them as significant as the two items discussed here, and actually a bit

more richly recorded as well -- that would be a lovely and appropriate completion of the

project of Tchaikovsky recording premieres made in America. And by way of encore,

Sevitzky’s pioneering recording of Kalinnikov’s First Symphony would probably

fit on the CD otherwise devoted to Tchaikovsky’s First, in the same key. |

Two other American orchestras active

on Victor in the early 1940s were those heard in very welcome restorations of the American

premiere recordings of two of Tchaikovsky’s early symphonies. On Guild GHCD 2422,

Eugene Goossens conducts the Cincinnati SO in the Symphony No.2 in C minor, Op.17 (the

"Little Russian"), and Hans Kindler conducts the orchestra he founded, the

National SO in Washington, in the Symphony No.3 in D major, Op.29 (known as the

"Polish" Symphony). These were hardly familiar works at the time these

recordings were made, although Igor Stravinsky, who had included material from No.3 in his

music for the ballet The Fairy’s Kiss, was at that time conducting the Second

Symphony in his concerts with American orchestras.

Two other American orchestras active

on Victor in the early 1940s were those heard in very welcome restorations of the American

premiere recordings of two of Tchaikovsky’s early symphonies. On Guild GHCD 2422,

Eugene Goossens conducts the Cincinnati SO in the Symphony No.2 in C minor, Op.17 (the

"Little Russian"), and Hans Kindler conducts the orchestra he founded, the

National SO in Washington, in the Symphony No.3 in D major, Op.29 (known as the

"Polish" Symphony). These were hardly familiar works at the time these

recordings were made, although Igor Stravinsky, who had included material from No.3 in his

music for the ballet The Fairy’s Kiss, was at that time conducting the Second

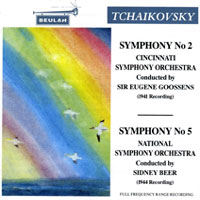

Symphony in his concerts with American orchestras. But the Goossens is definitely worth preserving, on more than merely historical

grounds, and the transfer on Guild is at least a tad more nearly adequate than an earlier

one, paired rather unimaginatively on a Beulah CD [Beulah 1PD11] with a capable but

unremarkable version of the Fifth Symphony with Sidney Beer conducting the National

Symphony Orchestra -- not the Washington orchestra heard in No.3 on the disc under

discussion here, but a London studio orchestra given that name by Decca in the early years

of ffrr. Guild definitely showed greater resourcefulness and judgment in its new

coupling.

But the Goossens is definitely worth preserving, on more than merely historical

grounds, and the transfer on Guild is at least a tad more nearly adequate than an earlier

one, paired rather unimaginatively on a Beulah CD [Beulah 1PD11] with a capable but

unremarkable version of the Fifth Symphony with Sidney Beer conducting the National

Symphony Orchestra -- not the Washington orchestra heard in No.3 on the disc under

discussion here, but a London studio orchestra given that name by Decca in the early years

of ffrr. Guild definitely showed greater resourcefulness and judgment in its new

coupling.