When Great Music Goes Bad

here’s an old, old joke about classical music and musicians that goes like this. Two players are tuning up in the rear row of the second violins. First player: "Done much since last weekend?" Second player: "Just a few midweek concerts in Manchester." First player: "What did you play?" Second player: "A couple of Beethoven symphonies, a bit of Tchaikovsky and some Brahms." First player: "Who was conducting?" Second player: "I didn’t notice."

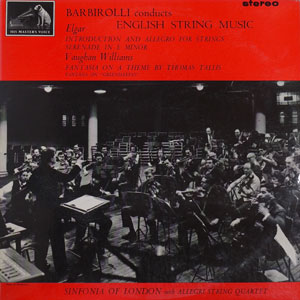

What could be better than a nice Sunday-afternoon concert with the Philharmonia? A simple, accessible program with something new, the unfamiliar (at least to me) Ireland Piano Concerto mixed with a few old favorites, including the Vaughan Williams Tallis Fantasia, a short piece I’ve always loved. As is the way with these things, Sunday concerts are often an opportunity for the second string to step up -- in this case that included the conductor. Opening with a bang (Walton’s Portsmouth Point Overture), the alarm bells were already ringing. If Walton is all about poise and juxtaposition, this was a shapeless cacophony -- our fearless, baton-wielding leader floating off in a transport of ecstasy as the orchestra tried to make sense of his windmill arms and "impressionistic" direction (I use the last term loosely). It was a situation that wasn’t helped by the presence of a new concert master, one who apparently confuses the roles of leader and soloist, reducing the normally impeccably drilled Philharmonia strings to a messy, ill-disciplined herd, vainly trying to follow his "expressive" lead. I can’t identify the exact point at which the orchestra decided to mutiny; it probably wasn’t a collective (or possibly even a conscious) decision -- more of a concerted drift -- but it soon became clear that the conductor was in one universe, the first violin in another, and the rest of the orchestra were just trying to get through. The Ireland was saved by the central role and anchor of the piano, but nothing prepared me for the catastrophic butchery that was about to be perpetrated on the Tallis. The Vaughn Williams is a deceptively simple piece that depends absolutely on the conductor’s control of tempo and intensity, the orchestra’s ability to play in concert. It is literally a string quartet writ large, requiring just that degree of intimate ensemble playing and controlled dynamic range. Get it right and it is compelling, dramatic and glorious. Get it wrong and it is trite and shapeless. Our two heroes got it so wrong that it was almost comical, with a tempo that was breathless where it should be measured, and a violinist who thought he was playing a concerto. The only light relief was watching (and hearing) the viola and cello first chairs playing their leader off the stage. I’ve never seen someone have a musical door slammed in his face before, but this could easily have caused a broken nose! The long drive home after a disappointing concert is usually a time for reflection. This time, it was a prolonged and groveling apology. Having assured Louise, my wife, that she’d love the Tallis, she was left bemused and deflated, probably questioning my critical faculties as well as her own. There was only one thing for it; arriving home, she put on the coffee while I warmed up the system. Settling down with cups in hand, we listened again to the Tallis -- but this time it was Barbirolli and the Sinfonia of London on EMI ASD 521, the seminal recording and performance of this work. Here was drama, tension, beauty, delicacy and contrast, scale and release. Here was a truly great performance, brought into our own home, with an impact and emotional connection that far exceeded the live performance we’d witnessed just hours before. What price the system’s second-fiddle status now? Okay, so I’m privileged to enjoy some spectacularly capable audio equipment -- and the Wilson Benesch Cardinal speakers that are currently in residence played no small part in the process -- but I’d argue that any well-sorted and moderately capable system could have eclipsed that concert experience. The reality is that whilst a great live performance is a thing of genuine power and wonder, live music is also a highly variable commodity. Sometimes it is great, and sometimes it isn’t. The advantage you enjoy with an audio system is that you can always count on the recording. Yes, the performance of your electronics will vary, and, yes, there are good recordings and bad ones, but you can work on your system and select your discs. In fact, it’s time to shrug off our inferiority complex and celebrate what audio systems can do. I can buy tickets to hear today’s great conductors or soloists, but my system can bring me Sir John, Sir Adrian, Herbert or Ella, Nina, Billie, Elvis (either one) or Robert (Cray, Wyatt, Smith or Zimmerman) -- and it can do it all on demand. I love live music; I recognize its virtue as a reference

point for system quality. But what I really love is the performance itself -- and

I really love the ability of great audio systems to deliver those performances on cue.

Sometimes it's easy to forget just how valuable an audio system can be. |

As audiophiles, we live in

an introspective little world, staring at our systems but looking outward at the wonders

of live music, ever comparing, ever measuring the re-creation at home against that

mythical original. Few would challenge the assertion that audio systems play a distinct

second fiddle when compared to the real thing. But occasionally, reality bites, upsetting

our cozy assumptions and nicely ordered universe. It bit me a few nights ago -- and the

wound is still smarting.

As audiophiles, we live in

an introspective little world, staring at our systems but looking outward at the wonders

of live music, ever comparing, ever measuring the re-creation at home against that

mythical original. Few would challenge the assertion that audio systems play a distinct

second fiddle when compared to the real thing. But occasionally, reality bites, upsetting

our cozy assumptions and nicely ordered universe. It bit me a few nights ago -- and the

wound is still smarting.