Four Play: Moving-Magnet Cartridges from Ortofon, The Cartridge Man, Nagaoka and VPI/SoundSmith

hese days it seems like a record isn’t a record unless it weighs 180 grams and costs over thirty dollars, and a cartridge isn’t serious unless it’s a high-priced moving-coil. But it wasn’t always that way. It’s easy to forget that moving-coils were once the minority cartridge choice: heavy, low of output and low of compliance, a poor match for the low-mass tonearms that were all the rage and the moving-magnet phono stages that were the default option back then. When the SME 111 and Shure V15 V represented the high-end benchmark, for most hi-fi enthusiasts the things that made the earth move were definitely magnets. I don’t go back quite that far, but even so, if you’d asked me when I started in retail whether MCs would ever achieve market dominance, I’d have still said no. But then things were on the move, a change was going to come and, at least as far as the UK was concerned, the world of record replay was never going to be the same again. Suddenly, we all needed fancy sprung turntables that flew in the face of accepted audiophile wisdom, that gave the press something to write about and dealers something to demonstrate. And while they were busy sweeping away the status quo, why not call time on those low-mass 'arms and high-compliance cartridges too. New needed to be different if it was going to be better -- and if all those old ‘tables were rubbish, then it stood to reason that all the bits that went with them were rubbish as well. It was a genuine revolution, one that overthrew the established order, installed a new government (almost) and consigned a whole generation of record-replay products to the dustbin of history. Almost overnight, rigid, medium-mass tonearms swept away the opposition, all with exotic Japanese (or Japanese-built) MCs mounted up front: SME, Hadcock and Mayware being replaced by Linn, Zeta, Syrinx and Alphason. No matter that those moving-coil cartridges demanded an extra stage of dedicated, solid-state amplification (or occasionally a transformer) -- that just justified the need for a new preamp. Why the history lesson? Because I for one don’t buy it -- and remember, I lived through it. If ever anybody got the full treatment, it was me, but even back then I smelt a rat. Nowadays, I look at the vinyl resurgence and I see mainly rigid turntables, some of them very high mass indeed. I see idler drives and direct drives. I see unipivot 'arms and even tonearms with knife-edge bearings -- both back from the dead. Yet somehow, the moving-magnet cartridge is still dismissed as inferior, a budget stopgap until you can afford a "real" cartridge, which will be a moving-coil, of course -- and that’s where a lot of listeners make their mistake. Not only do I believe that a good MM will stand comparison to some surprisingly expensive MCs, there are a whole lot of systems where it also makes a lot more sense to take the moving-magnet route. Don’t even get me started on the subject of high-output coils, a case of two rights making a wrong if ever there was one. Instead, let me just introduce you to my system, the logic that dictates my choices and a quartet of moving-magnet cartridges that will definitely do the business. The system that I use isn’t exactly normal audio-reviewer fare -- but then I’m not exactly an average reviewer. Not only is this the first "review" I’ve written, but this is the system I use day in, day out, my escape from wife, kids, grandkids and dogs. My listening room is the one room in the house they never enter, the system the one thing that I both own and they never touch. It’s built from an unusual and eclectic mix of equipment, pieces that have caught my ear over the years, products that have delivered something special and gone on doing it. Being a dealer and a distributor, I’ve had the inside track when it comes to price -- but that’s only after the wife, kids, grandkids and dog have emptied my wallet, so performance and value have been not just high on my personal list of priorities, they’ve been essential. Which helps explain the age, the exotic nature and the longevity of my equipment. No merry-go-round of exotic loaners here. This is kit that has been paid for and has to pay its way. I use a Clearlight Audio Recovery turntable, fitted with a recently acquired Wilson Benesch ACT 2 tonearm, which replaced an original Mission 774 low-mass model. The deck is around ten years old and well out of production, but it offers a Rega-compatible VTA base that can be adapted to take the ACT 2. The amplification is all tube and dates back some thirty years, built by Peter Bruty of Sound Design (and previously Croft) who sadly passed away a few years ago. The preamp has a built in moving-magnet phono stage (using two ECC83/12AX7 twin triodes) and a massive separate tube-regulated power supply (with 24 more tubes). The power amps are ugly, industrial looking things, large 150-watt OTL monoblocks utilizing ten EL509s per channel, but they sound great. These drive a pair of Raidho C1.1s, perched on their matching, wobbly stands. The equipment racks are blocky-but-effective homemade designs built from two-inch birch plywood and the whole lot is powered up and strung together with Nordost cables. I also use the excellent top-loading Helios Stargate to play CDs. The basement room is 16' x 13' with a dedicated mains supply and a solid concrete floor, the speakers firing down the length. It’s remarkably well-behaved despite a lowish ceiling, and I listen to mostly vocal, good pop, rock, and soul music with a small amount of blues and soft jazz thrown in for good measure. You’ll notice that classical music doesn’t figure on that list. That’s because I don’t play it. Tonearm and speakers apart, everything else is out of production, and if the company that made it still exists, its product line has probably moved on. In one sense that makes it a more real-world system than the one that many reviewers use. But there’s something else too. The popularity of single-ended amps and matching tubed preamps means that I’ve had to deal with just the same gain and matching issues that confront (and confuse) many an SET or low-powered-tube-amp owner. My OTLs may offer 150 watts into 8 ohms, but it’s nearer 65 into 4 ohms, and naff-all below that. That makes selecting a speaker super critical, in an attempt to balance drive characteristics, efficiency and dynamic range against the room size, system gain and the music played. It’s a challenge that SET owners will be familiar with. The tube preamp with its moving-magnet phono stage might also seem familiar. Tube preamps that can really handle low-output moving-coils without resorting to transformers or solid-state input stages are very few and far between. Of course, you can always use a standalone transformer, or even a complete standalone phono stage, but if you really want to keep things all tube, then there’s a better option -- the good, old moving-magnet. No extra boxes, extra cables or extra cost, and plenty of healthy, noise-free output. It makes me wonder why they ever went out of fashion. For this article I borrowed Roy Gregory's VPI Classic 2 turntable fitted with the JMW 10.5 tonearm and a number of interchangeable Classic armtubes. That allowed me to set up and optimize all four cartridges (as per the "Analog 101" Tech InSite) and then make swift changes among them. At least, that was the plan. After I’d set everything up, run them in and started listening to the cartridges, what should turn up but the new JMW 10.5 3D tonearm top. With two identical Music Maker III cartridges on hand, I mounted the second sample in the new armtube and compared it to the one I’d already mounted in the original, metal 'arm. I can’t swear in this review, which rather diminishes the impact of this experience, but the difference was huge! The new armtube was better in every way -- and not by a little bit. Lighter, with a lower effective mass and one-piece structure, it was so far ahead of an already good 'arm that I decided to ditch the multi-mount option and use the 3D armtube exclusively. This meant more work for me, but it made the differences much easier to hear and made each and every cartridge really sing, further underlining the point of this piece. So how do they sound? Well, firstly, they each make the case that moving-magnets are far from the dinosaurs that many audiophiles think they are. They all differ sonically, but in my opinion those differences simply mean that they will each suit some systems or listeners’ tastes better than others. None of them suffered any hum or noise problems with my valve phono stage and all were perfectly comfortable in both VPI tonearms as well as my Wilson Benesch. This first batch of cartridges all retail for under $1000, not exactly chicken feed but perfectly within range for newbie’s and seasoned audiophiles alike (not that any seasoned audiophile would ever consider these cartridges -- not expensive enough, not exclusive enough and not good enough; that’s audiophile logic: more expensive is of course always better, despite the system or the circumstances). Later, I’m hoping to look at some pricier alternatives that break the four-figure barrier, but for now our contenders are: Ortofon 2M Black ($799) The Ortofon is manufactured in Denmark by one of the biggest cartridge manufacturers still in business, making it the most widely available of these four models. It has a low-resonance composite body and expensive Shibata user-replaceable stylus. Ortofon also make a range of more affordable moving-magnet cartridges, as well as much more expensive high- and low-output moving-coils.

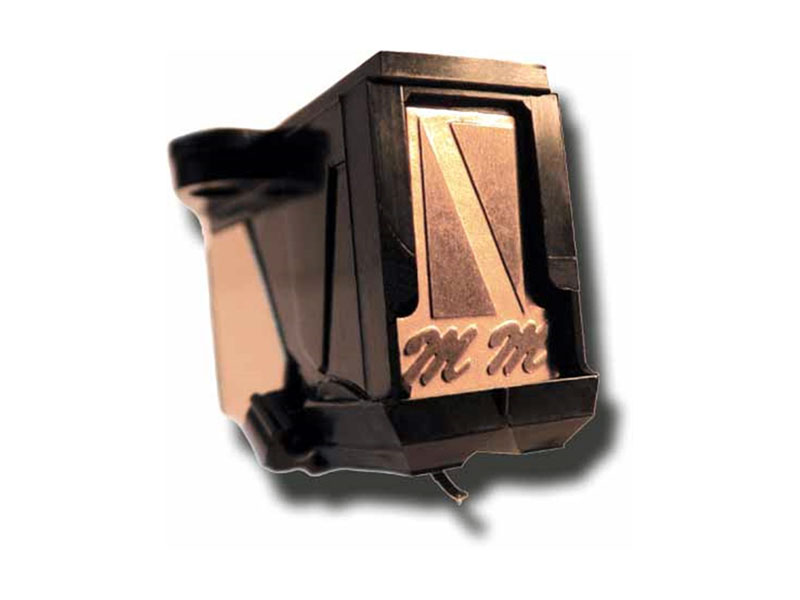

If you went for a demonstration/comparison of the cartridges covered in this article at your local hi-fi store, clutching an armful of 180-gram audiophile records, especially if you were new to vinyl and have been listening to CD for the last fifteen years, you would purchase the 2M Black over any of the others in a heartbeat. Its fast, wide-open, dynamic presentation will win it many friends on first listen. It manages to drag heaps of detail off of the disc and presents the musical information in a sonically spectacular, spot-lit way. It has nicely weighted, tight, dynamic bass. So what’s not to like, especially as it seems to do all the hi-fi things so well? Playing John Martyn’s "Stand Amazed" (from Heaven and Earth, a 180-gram pressing [Music On Vinyl MOVLP 405]) the Ortofon sounds like great hi-fi. It’s open, fast, detailed, vivid, full of vitality and sonically spectacular. But (and there’s always a but) Phil Collins' backing vocal on "Heel of the Hunt" sounded thin and washed out, while the soundstage was plenty wide but lacked any real depth. More worrying, John Martyn’s voice didn't sound like the gravelly, lived-in, characterful John Martyn that I know. Likewise, on "She’s Got A Ticket" (Tracy Chapman, self titled [UK Elektra EKT 44 960 744-1WE381]) the 2M Black was lightning fast with loads of bass slam and a really wide stage, but again the familiar vocals were thin and bleached. The overall presentation was detailed, quick and impressively transparent: great hi-fi with everything there but the soul, emotion and involvement that are what this album is all about. Both of these albums offer superb sound quality -- it’s one of the reasons that the Tracy Chapman album became almost annoyingly popular and why, if there were any justice, the John Martyn probably should. To hear the Ortofon at its best, you need music that’s nearer the norm -- congested, compressed and "radio mixed." The track "Metal and Dust" from the London Grammar album If You Wait [MADART1] is a perfect example. This music is modern, multi-layered and heavily processed, and the Ortofon managed to cut through the mix to create a clean, clear, wide soundstage with great layering and good bass depth, weight and impact. The result was a large and impressive sound that really made the music work. The most obvious shortcoming is a lack of warmth, soul or emotion -- just the things that normally draws you in with vinyl. Just like CD, its sound is slightly mechanical, a tad bright and tipped up -- very impressive but perhaps not musically satisfying in the long term. Of course, this may be just what you need if your system is a bit warm, rounded and lacking immediacy and excitement -- or if you just want to impress your mates. It does track the disc very well, but it seems to pick up loads of dirt and debris even from well-cleaned records. I would make an electronic or really good manual stylus cleaner a compulsory purchase with this cartridge if you intend to enjoy it as the manufacturer intended. That description might seem harsh, but then it’s measured against some pretty exacting standards. Compared to the average entry-level MC, the 2M Black is a nicely balanced, well-behaved and highly detailed little star. Its manners are impeccable and it's musically more involving and less mechanical than most of them. That (and its ready availability) is why it’s the benchmark model in both this article and the market. Cartridge Man Music Maker III (£550) If the Cartridge Man Music Maker III looks familiar, that’s because it is based on a Grado body and internals, so it looks exactly like those popular (and affordable) cartridges. But in this case the cantilever and diamond are far from standard. Assembled/manufactured in the UK by a small band of one, that would be Len Gregory (no relation to the editor), who likes doing it, even if it won’t make him rich (it makes him happy).

The Music Maker III is the polar opposite to the Ortofon: smooth, even-handed, a bit laid-back, with a soundstage a bit lacking in width but with plenty of depth. Vocals don’t project in the same way as with the 2M Black. Everything is warm, solid, relaxed and forgiving. Drums and cymbals lack that last bit of attack and bite and its presentation was not as wide or as spacious as the Ortofon’s. Instead it offers a greater sense of presence and color and a more coherent musical picture. On the John Martyn album, the Music Maker presented a softer picture with much more depth than the Ortofon (or the VPI Zephyr below), but the soundstage didn't get much wider than the speakers. Vocals were focused, clear and precise but lacked some immediacy.With Michael Hedges’ Aerial Boundaries [Windham Hill Records 371032-1], the Music Maker III’s overall coherence and sense of connected space really came into its own, with plenty of air, bite and depth. It lacked the attack, startling dynamics and vivid vitality of the 2M Black, but it gave a much greater sense of space to the reverb washed acoustic. The guitar might have sunk back into the soundfield, but that actually suits this recording and with pure acoustic recordings the Music Maker III gives by far the best impression of instruments in a single space. Even the Tracy Chapman album benefits from the effect, sounding open and well separated, with a quick bass that raises the tempo -- and the interest. In contrast, the London Grammar album sounded muffled and muddled, soft and a bit diffuse. The greater separation and insight offered by the Ortofon leaving the Music Maker III sounding less involving and informative than the other two. I used the Music Maker III with and without the company’s optional (extra cost) Isolator, a flexible mount that you fix between the cartridge body and the headshell. As far as I was concerned the decoupling wasn’t a success, and after a fairly brief experiment in both the VPI and Wilson Benesch 'arms, the Isolator was returned to its box, where it remains. Nagaoka MP-500 ($799) The Nagaoka MP-500 is manufactured in Japan and is the latest version of a design that has been around for ages (longer than me, and that’s saying something). It’s the top-of-the-line model and it has been tweaked, improved, and upgraded over the years. It also benefits from having a user-replaceable stylus.

The MP-500 is the vocal champ in this group, solo singers sitting bang in the middle of the stage with lovely warmth, air and believability, inviting you to listen intently to their song and their singing. It’s very, very engaging -- until the band picks up; then the soft, somewhat overripe bass kicks in, cymbals and bells shimmer and ring indistinctly in the background and guitars and keyboards merge and overlap. That solid vocal image and the congested soundstage are both symptoms of the MP-500’s presentation. Narrower and more bunched between the loudspeakers, it lacks space and separation -- but oh, those vocals. Tracy Chapman's voice sounded fantastic: natural and expressive with no hint of sibilance and right there in the room, center of the speakers. Unfortunately the bass was still slow and lethargic, which caused the music to lag, but even so, that voice was a thing to hear. Likewise, on the John Martyn album, the soundstage was the narrowest of the group, whereas the drums and cymbals with the other three cartridges covered here were fast and insistent. The Nagaoka lagged a long way behind, sounding somewhat sluggish and leggy. On the Michael Hedges album, the guitar lacked bite, sounding thickened and rounded with a distinct lack of air and space.To understand exactly how the MP-500 does what it does, you need an album like Rickie Lee Jones’s Flying Cowboys [Geffen UKWX 309924246-1] and the track "Ghost Train." It’s all about tension. RLJ’s vocals are shouty, nasal and harsh, yet the Nagaoka smoothed them out and removed the hard edges, did it without destroying the track’s atmosphere but at the cost of that tension. It’s almost as if the cartridge centers the structure of the music on the voice and everything else hangs off of it, rather than the rhythmic base built into the low frequencies. That central vocal performance certainly holds the attention, but it also makes the MP-500 the least evenly balanced of these cartridges. I can see some listeners falling in love with the beauty and centrality of its vocals, while others will find it rhythmically and musically opaque. VPI Zephyr ($999) The Zephyr is handmade for VPI in the USA by SoundSmith, loosely based on Bang & Olufsen moving-iron cartridges of old. This particular model equates to the second-most-expensive of the high-output range. Most unusually, SoundSmith's low-output cartridges are also moving-iron designs.

The Zephyr is vivid, fast and lucid. A very modern-sounding pickup, it has a very wide, deep and beautifully separated presentation akin to the Ortofon 2M Black's, but with more warmth and tonal color, more sense of rhythmic flow and way more soul, especially when it comes to vocals. It doesn’t retrieve the same amount of information as the Ortofon, but then none of the cartridges in this test does. What it does do is get right to the heart of the music. On "Ghost Train" this was the only cartridge that really captured the immediacy and tension, reproducing that edgy, raw vocal without destroying the track’s atmosphere and realism. Just like the Ortofon, it sorted through the London Grammar recording, capturing the inner layers and powerful bass, even if the 2M Black managed a little more air and detail up top. In contrast, Tracy Chapman’s voice sounded a little thin and lacking in that characteristic throaty warmth, even though she was well placed in a wide soundstage with quick, accurate dynamics and bass. John Martyn was suitably gruff and Aerial Boundaries was spectacular, treading just the right line between space and impact. The best all-'rounder here, the Zephyr is also the most expensive and had the advantage of being used with its own 'arm -- although truth be told, it was just as impressive in the Wilson Benesch ACT 2. Quick and clean, it also manages to sound warm, possibly as a result of its rounded, slightly muted top end. Even so this is a remarkably well-balanced cartridge and although it is quite a bit more expensive than the others here, it is also a serious deal compared to the more expensive competition, moving-coil or not.

hen it came to musical examples, I deliberately chose a range of different albums, some better recorded than others. Three are audiophile standards, two are straight out of your local store and each one presents its own challenges. They manage to illustrate the differences among these cartridges and their weaknesses, but also show how each one might suit a different listener or system. I did have on hand an extremely well-regarded, modern high-output moving-coil for reference. It had by far the best instruction manual I have ever read, but that wasn’t enough to elevate it above these four moving-magnet cartridges, at least not on musical grounds. It simply couldn’t match the power or dynamics of even the least dynamically impressive of the moving-magnets. That’s partly down to its lower output, but then that’s the normal situation. For all its detail and delicacy, it simply lacks the musical guts to get the job done. In theory, low-output moving-coils should leave these lowly moving-magnets in the dust, but that was not my experience. Given that you need to provide a step-up of some sort to go with them (I used a Tom Evans Groove, which should have given them every possible chance), comparing models at the same price isn’t really relevant, so I opted for a couple of popular designs from opposite ends of the sonic spectrum, the Denon DL-304 and the Audio-Technica AT-OC9/III. Both are available for around the $600 mark, although the Audio-Technica in particular lists for considerably more. The DL-304 is as polite as the conversation at a vicar’s tea party. Like almost all the other Denons I’ve ever used, it is warm and wooly, rounded and forgiving. I’ve eaten apples with more edges than the music coming out of this cartridge. It is slow and lacks any real sense of dynamics or timing, smoothing everything out to the point where I find it boring. If you’ve really got to tame down your system then maybe, but if your system needs this much taming, the chances are it’s got much bigger problems. The vintage DL-103 at least has a bit more get up and go, a bit more energy and a greater sense of power. The DL-304 is not horrible in all areas. The vocal delivery is somewhat like the Nagaoka's, just a bit thicker and denser, with less definition and looser bass. But as far as I’m concerned it is still hopelessly rounded and indistinct compared to a cartridge like the Zephyr, sluggish and lacking definition compared to the 2M Black.The original OC9 occupied a special place in my hi-fi past, almost single-handedly convincing me that there must be a better way. This latest iteration is no better. It is still bright, thin and lacking any kind of deep bass. Vocals were thin pinched and strident, with high-frequency percussion having a real fingernails-down-the-blackboard cringe factor. On a personal note, and if pressed, I would rather have a cartridge that veers to the brighter side of neutral rather than the other way, but I could not live with the OC9/III’s presentation. It is far too in your face, throwing everything at you in such a relentless, overly hyped, bright and forward way that I struggled to listen to it for any length of time. If it wasn’t for the responsibilities inherent in this article, it wouldn’t have survived in the system as long as it did -- and that wasn’t very long!Not surprisingly I would still definitely take the moving-magnet option in preference to any of the moving-coil alternatives I’ve just listed, at least with my setup, or a similar SET-based system. If I wanted fast and exciting, I would opt for the Ortofon or VPI (depending on budget); warm and relaxing it would be the Music Maker III, especially if I listened to mainly classical/acoustic music. The Nagaoka MP-500 is the wild card, a cartridge with particular strengths and a particular presentation that some listeners will love. Although I may seem to appear a bit hard on these

cartridges, I would use any of them over any comparably priced high- or low-output

moving-coil. I think each of these cartridges could suit a different listener or

situation, but what’s obvious to me is that this type of cartridge is far too good to

be overlooked in a high-quality audio system. There’s clearly life still in the

moving-magnet cartridge and if none of these cartridges will match a top-end moving coil

for finesse and absolute sonic accuracy, they only cost a quarter of the price asked for a

decent moving-coil -- and around a twentieth of the price tag that gets stuck on the very

best. What they will do is deliver real music in real-world systems and at real-world

prices -- and without the need for a really expensive step-up transformer. For how many

moving-coils can you make that claim? |