First Sounds: Lyra Atlas Lambda

any of us audiophiles have purchased a “last” component at one time or another. Some, like CD players, aren’t receiving the attention they used to from designers and manufacturers, so owners of large CD collections want to get that final upgrade while players are still available. In other cases, we’ve scrimped and saved to finally get the amplifier or turntable of our dreams, and we all know this one product will last longer than our hearing acuity. Phono cartridges are another matter entirely. No matter whether you are talking about a budget model or the state of the art, a cartridge wears out. The phrase “nothing lasts forever” may have been coined with phono cartridges in mind. Even if you use a moving-magnet cartridge, you are going to need to replace the stylus assembly on occasion, and then you are sometimes presented the option to upgrade from a stock stylus to something a little sexier. Whether you are moving up to a better cartridge or just replacing a worn-out model, there is always a new cartridge in your future. Recently, Lyra updated its Atlas cartridge, which I've been using since shortly after it was introduced. I was surprised at just how venerable the Atlas had become and how many other cartridges had come and gone without unseating it as a favorite. Sure, I have a handful of items, like VPI bricks and a stylus demagnetizer, that have outlasted the Atlas in my system and a handful of older cartridges in my stereo kit. But apart from such peripherals and a few retired cartridges standing by for emergencies, the Atlas is the single most long-lasting component active in my system. The Atlas performed without complaint for seven years before Lyra introduced the new Lambda version. I’ve been asked how many hours I’ve put on my Atlas, and all I can say is "lots." Life is too short to count hours of cartridge use. I’ve read recommendations that a cartridge should be swapped out from everywhere between a thousand and three thousand hours, but after seven years, I could detect no damage viewing the stylus under a microscope, nor did I hear any significant degradation by ear. Lyra has long offered a well-balanced line of higher-end cartridges, with prices for today’s models starting at a couple of thousand dollars and scaling up to $12,000. The earlier incarnation of Lyra’s product line was rolled out beginning in 2012 with what designer Jonathan Carr called the “New Angle” models: the Delos, Kleos, Etna and Atlas. The flagship Atlas, which I reviewed in its original configuration, was the first New Angle design. A few years later, Lyra released its Etna. The Etna exhibited a different palette of attributes than the Atlas, giving up some of that cartridge’s agility and muscle for a greater sense of grace. Lyra has now updated its Atlas and Etna models, but rather than renaming them, they have appended Lambda to each of the established names.

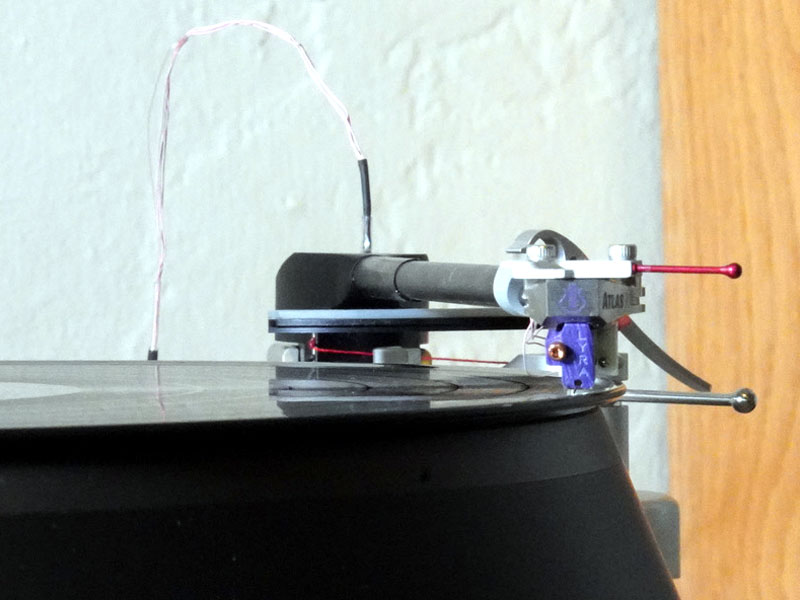

The Lambda refinement builds on the New Angle models’ tapered dampers used to pre-load the cantilever downward, so that the application of vertical tracking force will align the coil angle with the magnets when the cartridge is in playing position. The Lambda versions separate the tapered dampers into flat elastomer damping discs and add a support "pillow" to serve as the cantilever pre-loading element. The new dampers allow the Lambda versions to follow the intent of Carr’s original design more precisely and allow master craftsman Yoshinori Mishima to build each cartridge to a tighter and more consistent tolerance. Tighter tolerances mean that the cantilever can be more reliably centered in its intended position. This improvement is said to significantly improve the stability and sonic performance of the cartridges. Outwardly, the Atlas cartridge body has changed little, with the color accent moving from emerald green to purple. The tracking force and other settings are still the same. Indeed, the specification sheet for the Lambda appears to be the same as that of the original Atlas. The price of the Atlas Lambda is $11,995; for those with an Atlas, the upgrade path to Lambda is $5995. Once the Atlas Lambda was broken in for about fifty hours, the differences between it and the original Atlas were evident. I’ve been recently enjoying the piano recordings of VŪkingur ”laffson on Deutsche Grammophon, and especially his most recent release, Debussy-Rameau [Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft 483 8383]. With the standard Atlas, the recording is splendid, and not bass-shy, like Deutsche Grammophon releases of decades past. The first thing I noticed with the Lambda -- an increase in texture -- was unexpected. Just as great composition can provide a sense of texture, in the choice of instruments and the way orchestral lines are constructed, proper reproduction of recorded music brings out the music’s depth, the irregularities of the texture of the tonal qualities that are lost when compromises are made. Whether its first-class mastering or top-drawer equipment, what we as audiophiles strive for (among many other things) is capturing the depth, detail and clarity of musical texture. The Atlas Lambda was exceptional in that regard, providing a greater sense of each note's pitch and timbre than its predecessor. ”laffson’s tonal quality isn’t lush and the Atlas Lambda doesn’t make it so. What it does do is make the music sound more alive. The Lambda has lost none of the Atlas’s speed and muscle, so the piano sound not only had proper texture but also proper definition and weight, because the Lambda more accuracy reproduced the duration and intensity of each note. The ability to capture the weight and feel of the music was not limited to solo instrumental recordings. Stravinsky's Pulcinella as performed by the Academy of St. Martin In The Fields, Neville Marriner conducting, [Argo ZRG 575] is among the greatest-sounding Kingsway Hall Decca recordings, and it sounds at least good on almost any decent system. But the Atlas Lambda transcended "good" -- the improvements in tonal quality from the standard Atlas to the Lambda were obvious on a recording like this. The instrumental placement was remarkably stable, and the tonal accuracy was in razor-sharp focus. Feeling that this recording was too easy a test, I turned to something more challenging -- Karajan’s Deutsche Grammophon recordings of the Beethoven's symphonies [Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft SKL 101-8]. No Kingsway Hall or Kenneth Wilkinson here to create a recording that might sound good on any system. My 1963 copy, although in pristine visual condition, always seemed to go slightly off the rails every now and again, with the strings collapsing into a compressed, flat glop. Every other cartridge (including the Atlas) over the years had the same issue -- what seemed to be the occasional tracking problem with Symphony No. 7. The Lambda didn’t turn the Deutsche Grammophon into a Decca, but it did sort out the string section like no other. Now, the violins especially retained their separation and didn’t collapse into one another. Stepping up from there to a true torture test, I pulled out one of my favorite Baroque recordings using original instruments: the Bach Overtures (aka Orchestral Suites) with Nicolaus Harnoncourt leading the Concentus Musicus Wien [Telefunken SAWT 9509/10]. My black-and-gold-label originals are scoffed at by audiophiles, and I can remember one good friend once asking why I kept those old Telefunken boxes taking up valuable shelf space. With the improvements in cartridges over the decades, however, these recordings just keep sounding better. The original Atlas, especially when mated to a solid-state phono section, could sound slightly harsh in some places. The Lambda Atlas has integrated at least some of the Etna’s top-end grace with the Atlas’s speed and muscle and resolves this occasional top-end edginess. Sure, if you set your vertical tracking angle wrong, you can still get that ear-melting sound of original instruments, but you won’t need a microscope to tell you when it’s set right when you hear the violins enter the fray in Suites 3 and 4. The record I most looked forward to hearing once the Atlas Lambda broke in was Gillian Welch’s The Harrow & The Harvest [Acony 1 109LP]. Beside her commitment to all-analog recording and mastering, Welch, whose work flows from the bluegrass roots of Bill Monroe, is a force to be reckoned with in modern country music. The music and the sound of this LP are top-drawer. Last year for some months I had a Fuuga moving-coil cartridge mounted in one of my tonearms and compared it to the original Atlas on a dozen or so recordings. The Fuuga is an outstanding cartridge and played toe-to-toe with the slightly more expensive Atlas. There were always differences between the way the two cartridges sounded on each record, but the Gillian Welch LP magnified these differences to the point of making it seem like I was listening to the same recording mastered by two different engineers. The differences in the Welch record were all in favor of the Fuuga’s rendition, which sounded more graceful, more musical. The Atlas Lambda was more sympathetic to vocals than the original Atlas and injected a breath of life into the sound of vocal reproduction of the human voice, which was slightly missing with the original version. Listen to the sound of the voice and banjo on "Dark Turn of Mind" and you can’t help but notice that the Lambda has filled in some of the blanks on that sound canvas. Is it as good as the Fuuga on this recording? Let’s just say that it's better than the original Atlas. The improvements I hear in the cartridge’s reproduction of voices on the Welch disc are consistent across the board with vocal recordings. Pull almost any Ella Fitzgerald record off the shelf, and you may notice that the Lambda has shifted ever so slightly to the lushness of a Koetsu, but lush without slush because of the cartridge’s speed and precision. Johnny Cash’s voice sounds fuller on Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison [Columbia CS 9639], and the combination of more detailed texture with Atlas speed and muscle makes the live recording sound more real than I have ever heard it before. (I’ve attended prison concerts -- San Quentin if not Folsom -- and am familiar with the energy of such a concert.) Yes, the Atlas’s original muscle is still there and may sound a bit more robust at times because of the almost tactile improvement in texture. Whether it’s Black Sabbath’s Paranoid [Warner Bros 3104] or The Who’s Who’s Next [Track 2408 102] or dueling electric guitars on Friday Night In San Francisco [Columbia/Impex IMP6031-45], the Lambda is just as muscular and lightning-fast as its predecessor. If anything, the Lambda has an edge on the original Atlas when it comes to dynamics. Even with smaller-scale albums, the improvements in speed and snap were obvious. I’ve never heard Joe Morello’s drum solo on "Take Five" sound so whip-sharp and dynamic (Dave Brubeck's Time Out [Columbia CS 8192]).

For me, the Atlas Lambda is Jonathan Carr and Yoshinori

Mishima’s masterpiece -- a "last" cartridge for the most discriminating

audiophile. Anyone with the money to buy one of these extraordinary cartridges, however,

will surely have multiple armwands, so let’s just say that if you are one of these

lucky few, there is little risk to hitching an Atlas Lambda to one of them and settling

back for some fun. As I said with the original Atlas, if I had to start from scratch and

build a system around one component, it would be that cartridge. But now it would be the

Atlas Lambda. |