Beethoven's Triple Concerto: Why Slum It with One Soloist When You Can

Live It Up with Three?

ver since orchestras have grown beyond twenty seats, the concerto has presented conductors and leaders with the sort of balancing act that might daunt even The Flying Wallendas. A piano might have a fighting chance against a smallish orchestra, but a solo violin? Ironically, throw in a couple of extra soloists and all too often you are actually creating an even more complex problem -- and making matters worse.

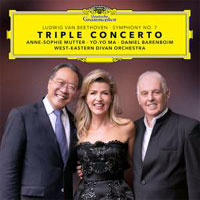

Now add the fact that not only did Mutter and Ma commit an earlier version of the Triple Concerto to disc, but that that recording is also currently available as an 180-gram pressing from Deutsche Grammophon [Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft 483 8246] and the plot thickens. That performance dates from 1980 (with pianist Mark Zeltser, Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker), capturing the star soloists at the start of their careers. And the cherry on the icing on the cake? The long-accepted, go-to performance of the Triple, recorded by EMI in 1969 [EMI ASD 2582] with a stellar lineup featuring David Oistrakh, Rostropovich and Richter, also featuring none other than -- you guessed it -- Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker, was re-released by Warner Music on 180-gram vinyl in 2017 [Warner Classics 0190295282066] and is also still available!

The success of this project depends in no small part on the nature and quality of the violinist’s contribution. In recent years, Mutter has almost visibly and audibly grown in confidence, almost as if she has finally shrugged off the wunderkind label and blossomed into her own character. Listen to this latest recording in comparison to those earlier versions and it is immediately apparent that her singular confidence and maturity allow her to comfortably follow and respond to Ma’s lead, to considerable musical effect. Forty years ago, the two seemed locked in competition, both with each other and Karajan’s typically stentorian and overbearing orchestral accompaniment. The level of musical intimacy and understanding of the current performance and belies the fact that the two haven’t shared a stage (or a studio) in the intervening years. It should come as no surprise that Barenboim’s piano lack’s the fundamental authority and artistic tension that Richter achieves, but the lightness of touch he brings to the orchestral direction, combined with the youthful enthusiasm of the live performance, makes this a joyously captivating musical event. The recording is typical of Deutsche Grammophon’s better current efforts. The discs are beautifully pressed, with dead-flat, silent surfaces and a refreshingly open and richly shaded sound, good dynamic range and a slightly warm overall balance that suits the music perfectly. It’s a stark contrast to Deutsche Grammophon’s 1980 recording, where the soloists were almost submerged within (and occasionally beneath) the BPO. Here they are placed front and center, arguably slightly over-voiced, but the end result is as engaging as it is pleasing.

I know that individually the soloists can’t compete. I know that the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra can’t match the scale or flawless ensemble of the BPO. I know that if you can keep him in his box, Karajan can deliver a sense of orchestral power and authority that few can match. But the freshness, energy, vivacity and dynamic layering of the live performance, the greater agility of its smaller-scale forces and the inescapable sense of live performers having fun (this was a gala performance, celebrating 20 years of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra), all make the newer performance a very welcome arrival indeed. Does it supersede the established reference? It’s a better recording/pressing (at least if you compare the current versions), and it includes an equally engaging and enjoyable performance of the Seventh Symphony, one that might not rewrite the understanding of the work but certainly reveals new insights into its structure and humor. If a large part of classical music’s fascination

lies in different readings and different performances of the same work, then the

conclusion here is simple: you should own both the new DGG and older EMI recordings.

Listening to the one will only increase your appreciation of the other, and your

understanding of the works as a whole. If you already own the EMI, this new Deutsche

Grammophon recording is well worth adding to your collection. If you don’t, then this

double album is a great place to start. |

So perhaps it is no surprise that Beethoven’s Triple Concerto for violin,

cello and piano has long been regarded as one of his weaker and more problematic

compositions, a view that has only recently been rehabilitated with its recognition as a

key formal stepping stone toward such important pieces as the Fidelio Overture,

as well as the violin and later piano concertos. This was the work in which he first

resolved the structural relationship between orchestra and solo instrument that we now

take for granted. Ten years ago, this release would probably have provoked a very

different reaction: “Who needs another Seventh Symphony and who actually needs the

Triple Concerto at all?” But take Anne-Sophie Mutter, Yo-Yo Ma and Daniel Barenboim

performing the Triple [Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft 2531 262], throw in the growing

interest in performing the Beethoven symphonies with smaller orchestral forces and you

have a potentially intriguing coupling.

So perhaps it is no surprise that Beethoven’s Triple Concerto for violin,

cello and piano has long been regarded as one of his weaker and more problematic

compositions, a view that has only recently been rehabilitated with its recognition as a

key formal stepping stone toward such important pieces as the Fidelio Overture,

as well as the violin and later piano concertos. This was the work in which he first

resolved the structural relationship between orchestra and solo instrument that we now

take for granted. Ten years ago, this release would probably have provoked a very

different reaction: “Who needs another Seventh Symphony and who actually needs the

Triple Concerto at all?” But take Anne-Sophie Mutter, Yo-Yo Ma and Daniel Barenboim

performing the Triple [Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft 2531 262], throw in the growing

interest in performing the Beethoven symphonies with smaller orchestral forces and you

have a potentially intriguing coupling. But if any concerto is a compositional and performance tightrope that must

balance the competing interests of soloist and orchestra, how do you balance the competing

interests (and egos) of three separate soloists? That question alone helps explain the

Triple Concerto’s distinctly checkered recording history, as well as helping us

appreciate the qualities of this latest recording. It also helps to understand that, in

truth, the term "Triple" is something of a misnomer. Achieving a perfect musical

conversation among violin, cello and piano was always going to be a stretch, and, in

practice, it is the cello that leads the discussion and commands the center ground. Rather

than attempting to balance the three solo instruments (and those jostling egos of the star

performers all too often drafted in to play the piece), allowing the cello’s primacy

brings a sense of coherent purpose and direction to proceedings, opening up the

conversational opportunities with the other two solo instruments.

But if any concerto is a compositional and performance tightrope that must

balance the competing interests of soloist and orchestra, how do you balance the competing

interests (and egos) of three separate soloists? That question alone helps explain the

Triple Concerto’s distinctly checkered recording history, as well as helping us

appreciate the qualities of this latest recording. It also helps to understand that, in

truth, the term "Triple" is something of a misnomer. Achieving a perfect musical

conversation among violin, cello and piano was always going to be a stretch, and, in

practice, it is the cello that leads the discussion and commands the center ground. Rather

than attempting to balance the three solo instruments (and those jostling egos of the star

performers all too often drafted in to play the piece), allowing the cello’s primacy

brings a sense of coherent purpose and direction to proceedings, opening up the

conversational opportunities with the other two solo instruments. How does this new recording stack

up against the 1969 EMI benchmark? Amongst the many all-star casts to record the work back

in the '60s and '70s, Oistrakh, Rostropovich and Richter was by far the most successful.

Perhaps that’s a result of the soloists’ shared Soviet heritage; perhaps

it’s to do with their own sense of artistic security, each at the top of their game;

or perhaps most tellingly of all, because it's an EMI recording, Karajan didn’t have

the same influence over the process and production. Indeed, if anybody had an ego to

compete with HvK, it was probably producer Walter Legge. Either way, the recording places

the soloists well to the fore, preventing them from being overpowered by the BPO’s

sumptuous playing. Rostropovich establishes an early command, Oistrakh responds with deft

sensitivity, and Richter’s piano is a revelation. It’s not surprising that half

a century later this performance still sets the standard.

How does this new recording stack

up against the 1969 EMI benchmark? Amongst the many all-star casts to record the work back

in the '60s and '70s, Oistrakh, Rostropovich and Richter was by far the most successful.

Perhaps that’s a result of the soloists’ shared Soviet heritage; perhaps

it’s to do with their own sense of artistic security, each at the top of their game;

or perhaps most tellingly of all, because it's an EMI recording, Karajan didn’t have

the same influence over the process and production. Indeed, if anybody had an ego to

compete with HvK, it was probably producer Walter Legge. Either way, the recording places

the soloists well to the fore, preventing them from being overpowered by the BPO’s

sumptuous playing. Rostropovich establishes an early command, Oistrakh responds with deft

sensitivity, and Richter’s piano is a revelation. It’s not surprising that half

a century later this performance still sets the standard.