The Brave New World of System Optimization

tirling Trayle is a system optimizer. He’s a guy you pay to come to your home and improve the performance of your audio system. Why would you pay somebody to do that -- and why now? After all, we all know how to set up our systems, don’t we? Besides which, we never had to pay in the past. Well, I think that more and more of us are going to be paying in the future and that pretty soon our system optimizer, our "setup guy," is going to become a vital component in any serious, performance-orientated audio system, just as much an essential product as the amplifier that drives the speakers.

To understand why the introduction of this extra cost isn’t just necessary but actually makes perfect sense, we need to look at how our industry and how we buy our systems have changed. As I said, there are two questions -- why and why now? So let’s look at the second one first. Genuinely new product categories are rare as hen’s teeth. With nothing (or at least, very little) new under the audio sun, the vast majority of "new" product types are really reinventions or reapplications, doing the same thing differently or doing something new but in the same old way. That’s definitely the case with the system optimizer. There’s nothing new about what this product does, and it doesn’t do anything (or not much) that differently from the way it has been done in the past. But what is different is how you access it and whom you pay for it. The times, as we are fond of saying, are a-changin’, and as they change the way we go about the audio business changes too. The way we buy audio equipment and the music we play through it has been transformed by the fact of and the technology underpinning the Internet. Just look at record collecting. Once it was a case of endlessly rifling through racks of old records in the hope of unearthing that hidden gem. Now, you just go online, look at the offerings and decide how much you want to pay. Once upon a time you would have been reading these words printed in a magazine you’d paid for, rather than free on the Internet. Music downloads tell their own story. But the real impact on the industry is in the twin realms of customer access and price parity. It used to be that buying hi-fi equipment was done through dealers, who in turn dealt with distributors or sometimes, in their home markets, directly with manufacturers. Each step in the process added its own value and associated costs. The manufacturer designed and built the product. The distributor held local stock, managed press and punters, and took care of product servicing -- adding a percentage to what then became the trade price for that pleasure. The dealer invested in premises and stock, demonstrating and advising on those products so that we, the end users, could compare them and choose which ones we wanted to buy, whereupon the dealer would install said product into our home system -- also adding a percentage along the way. All of which is a model of how retail sales worked the world over. It’s fine as long as everybody does his bit and adds the value (and absorbs the costs) that he is supposed to. But there are a number of problems that emerge if that doesn’t happen -- and those problems do emerge as soon as people get greedy. It starts with us, the customers. We want a discount -- partly because everybody is busy telling us we should. Once upon a time that wasn’t such a big deal. Audio dealers always lost out on the odd sale to a competitor who was prepared to undercut them and a customer who was prepared to travel. That’s competition. But the Internet has changed all that. Not only can customers compare prices at the click of a mouse, they can look at the price of products in their home market -- conveniently forgetting the cost of shipping, duties and variations in local tax along the way. They can also compare prices without worrying about comparing like with like. So a warehouse mail-order supplier has a very different cost structure to your local brick-and-mortar dealer -- but the Internet, or at least the person looking at it, doesn’t differentiate. He (it’s nearly always a he) is only interested in the bottom-line figure, often quite willing to use the facilities and staff at his local store, drink their coffee and then use the prices he got off the Internet to score a discount, without stopping to consider who is paying for the room he’s just been sitting in or for that guy who changes the cables and plays the discs.

I don’t want to get too buried in the ins and outs of this, but the overall effect is to create massive price pressure in the retail sector. The effect of that is that dealers need more and more margin (in order to offer "acceptable" discounts) and have less and less money to invest in adding the value they are supposed to provide. That means they are less willing to install, can spend less on staff training, and, critically, they have less money to spend on stock, which in turn means that they actually floor and demonstrate fewer products. Now consider this: to make a product into a commercially viable stock item, a dealer has to sell three a year -- and that’s just to break even. Forget profit margins on products; what you need to think about is actual profit after overhead. A retailer has to invest in stock, premises, utilities and taxes, staff and payroll costs plus myriad other expenses. By the time he has paid his bills his bottom-line profit will probably amount to somewhere between 4% and 6% of turnover. Just think about that the next time you are confidently expecting a 10 or 15 percent discount. Now let’s look at it through the other end of the telescope. The manufacturer (any manufacturer, let alone a startup) now finds it increasingly difficult to get product into dealers, while those dealers now hold less and less stock. That means the manufacturer now has to take on the costs of accumulating and storing that stock. What’s more, many dealers can no longer afford to floor a full line. After all, how many Wilson dealers stock XLFs, Magico dealers stock Q7s, or Focal dealers stock Grandes? Increasingly, the costs of supporting those products in the marketplace are being born by the manufacturers or distributors -- and not just the cost of the product, but the expertise needed to work with it too -- all while retail-price pressure is shrinking margins. If we look for a moment at those $100,000-plus loudspeakers, how many dealers will actually sell three or more pairs a year -- and at full price, because discounts reduce profits? Now look at who makes the money on any sales there are. Say the product sells for $100,000 to keep the sums simple. The dealer might pay $60,000 to the distributor, who probably pays the manufacturer around $35,000. You have to take the costs and taxes out of those margins -- but the manufacturer has to actually build the thing. Bottom line? The person who actually makes the product is the one getting the least money from each sale. At the same time, that person is having to shoulder more of the costs and having more difficulty getting products in front of the public -- because dealers can’t afford to stock them. You don’t have to be Einstein to work out that something has to give. In fact, it’s been slowly edging towards catastrophic change for quite a while. The picture I’ve painted is simplistic and generalized, but just like a cartoon, the basic outline holds true. Some companies have been far more successful than others when it comes to maintaining their retail network and dealer base. But others have found themselves essentially locked out of the dealers. They might be established manufacturers who have fallen away in terms of profile or popularity, or they might be newcomers who have never managed (or in some cases, never wanted to) get their foot in the door. This is where the Internet comes in, allowing those manufacturers to deal directly with a global market. Of course, it’s not quite that simple. Somebody making a $300 headphone amp is in a very different situation to a big-name brand with a $15,000 preamp or $50,000 speaker. People generally want to hear those big-buck products before purchase unless -- unless the reputation is good enough and the price is low enough. A manufacturer or distributor can offer a 30 percent discount and still make more money than he normally would under the old model -- and in the case of the manufacturer, considerably more. And because the Internet is global, it only takes a few serious manufacturers to choose or be forced down this route, and the foundations of the whole edifice start to crumble. Believe me, we are fast approaching critical mass.

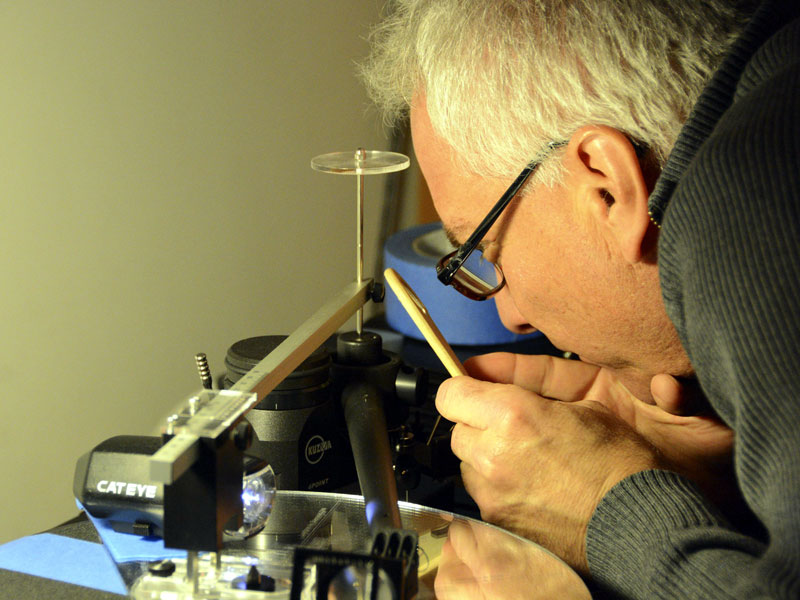

At this point, you might well be rubbing your hands in glee at the idea of the cost of high-end ownership being slashed. Prices might drop by 30 percent or even as much as 50 percent. But what are you giving up along the way? Now’s a good time to remind ourselves that it isn’t the equipment involved that makes a system high-end but the sound it produces. Dealers aren’t just about demonstration. Their other major contribution to the process is setting up and tuning the system/equipment so that it actually delivers its musical potential. It’s a contribution that is largely invisible and massively underrated -- partly because fewer and fewer dealers have the inclination or capability to carry it out. Nor is it a void that the vast majority of manufacturers can fill. Bypass the dealer and the fact is that you find yourself largely on your own when it comes to system setup. So what, you might well be thinking. How difficult is it to set up a power amp? That’s a question we’ll be looking at later, and the answer will probably surprise you. But that’s because it’s time to stop kidding ourselves. When it comes to setting up systems, the vast majority of people really haven’t a clue. I’m not talking about wiring it so that it makes sound. I’m talking about squeezing every last ounce of energy and performance out of a system, performance that, in theory at least, you’ve already paid for -- or maybe not. Tuning systems is a way, way more involved and precise process than most customers realize -- because most customers have never experienced it being done. It depends on ability, practice, experience and more experience. I’ve been doing this for thirty years, day in, day out, as a job, not part time or as a hobby. I’m still learning, almost every day. If you ever think you know it all or that you’ve extracted everything a system can deliver, you are deluding yourself. But I know a man who can wring the last ounce of performance out of an audio system -- well, I know a man who gets pretty darn close. Back in the day, dealers in the UK were an almost godlike presence. You worked your way up the Linn/Naim system ladder and the last thing you did was touch anything but the volume control. If anything needed shifting, moving, adjusting or swapping -- that’s what your dealer was for. And woe betide the hapless customer whose system was found to be out of whack. "Have you moved this?" was not a question, more of an interrogation. Back then, customers used to get struck off. How times have changed. Nowadays, if you have a Linn or Naim system and you are serious about getting the best out of it, you can do a lot worse than call Peter Swain at Cymbiosis. Peter literally travels the world tuning people’s systems -- at a price. He really only works with Linn and Naim equipment, but even in as circumscribed and diligently supported environment as this, he is able to transform the performance of the systems he works on, as his glowing testimonials and the plethora of incredibly positive Internet reports attest. Peter is a system optimizer, even if that’s not a term he’d recognize or use. Look at your own system and it probably contains a mix of equipment, sourced from several different dealers, maybe a bit of secondhand kit or equipment bought off of the Internet. It might well have moved house (bits of it several times) and, frankly, along the way it has probably lost any last vestiges of its initial setup, even if it ever had one. Now tot up the funds invested (I know, it hurts) and ask yourself realistically whether you think it sounds as good as it could or even as good as it should. Finally, ask yourself what it might be worth to get it working properly and just how big that difference would be. That’s exactly where Stirling Trayle of Audio Systems Optimized comes in, audio gun for hire, living example of a new product offering, the system optimizer. What makes Mr. Trayle think he’s qualified for the job? After all, there really are no formal training schemes, certificates or qualifications when it comes to audio setup and system optimization. Instead, it’s a case of learning on the job and accumulating experience. But to go that extra mile and get really superior results, you need to be that peculiar kind of person who rationalizes, organizes and analyzes those experiences, codifying them into a strategy that is systematic enough yet also flexible enough to embrace almost any set of circumstances. It means taking system setup back to first principles. If you are Cymbiosis working with a specific set of equipment with its own internal logic and prescribed setup approaches, that narrowing of the scope is a huge advantage. But the US market in which Audio Systems Optimized is based and the global market in which it plies its trade has never been so disciplined. Peter Swain has a good idea of what he’s getting himself into before he arrives at a customer’s house; Stirling Trayle could be presented with almost anything. How do you know that he’s really qualified to work with that special selection of kit that’s so close to your heart? It’s a crucial question -- and one that we are going to address in time-honored audio fashion: by conducting a review -- just as we’d review an amplifier, a turntable, speakers or any other part of your system. Because that’s what system optimization is -- a crucial part of getting the best out of any system. We’ll look at the background, the history and we’ll test capabilities and performance -- in a variety of different situations and system contexts. As I said, genuinely new product categories are as rare as hen’s teeth. Quite often they require some explanation or an adjustment in our thinking to understand their potential importance. A system is so much more than an assorted collection of hardware. The way that it’s put together and arranged, the infrastructure that feeds it, supports it and binds it into a single, coherent whole is what makes it greater than the sum of its parts. That’s not a given, and it’s no longer a guaranteed part of purchasing the equipment in the first place -- which means you need to buy in, just like cables, supports or the equipment itself. The more we all depend on direct sales, buying over the Internet to cut prices or buying used, the more of that input we are all going to need -- which is why, increasingly, the system optimizer is the one crucial component we can least do without. If you’ve read this far, consider the notion

explained and your current thinking at least questioned if not actually adjusted. Next up,

the review. |